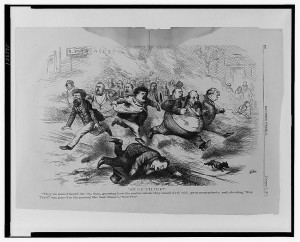

“Thief!” “Fire!” “Wolf!”

All three are examples of an ancient form of alarm called the “hue and cry.” A cry for help and assistance in response to crime or danger was an integral part of historical law enforcement. Statutes or regulations in several European countries required citizens to respond to the hue and cry. They had to hunt down the criminal or wolf or help put out the fire.

Just how prevalent was the hue and cry in Europe? A brief peak in the literature suggests it was quite widespread. In England, the Statute of Winchester (1 Edward 14, 1885) charged townsfolk to pursue a criminal if they heard the cry. Germans used the hue and cry by shouting, “Zeter und Mordio!” A 13th c. criminal code called the Sachsenspiegel also required the court proceedings against a murderer to open with the cry. In France, a victim hollered “haro,” “harou,” or “harue.” “Accor’uomo!” was the cry in Italy. Spain also raised their version of the hue and cry in response to a crime (but I can’t find what words the Spaniards used). Hungary, in a part that is now Romania, raised the alarm by shouting out “Tolvaj!” (thief) or “Tulai!” (help).

Settlers transported the hue and cry to colonial America. Boston, New York, and Philadelphia all employed it. In New York, police shook wooden rattles to raise the cry. But for sparsely populated regions such as rural Virginia, the old European custom proved inadequate. All in all, given that crying out for help and assisting in emergencies are such natural, human responses, it is not at all surprising that the custom was widespread and formalized.

The multiplicity of the languages makes it hard to research the prevalence of the hue and cry in Europe. If you have anything to add, please join in on the discussion!

Text © Ann Marie Ackermann, September 2014; Images: morugeFile, shutterstock.com & National Archives. See Impressum.

Some literature on point:

Emise Bálint, Mechanisms of the Hue and Cry in Kolozsvár in the Second Half of the Sixteenth Century, in Cultural History of Early Modern European Streets (Riitta Laitinen & Thomas V. Cohen, eds.; (Ledien, Bosten: Brill 2009) p. 40.

Gesa Dane. “Zeter und Mordio”: Vergewaltigung in Literatur und Recht (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag 2005) pp. 22-23.

A. Esmein. A History of Continental Criminal Procedure with Special Reference to France ( Boston: Little, Brown & Co. 1913) p. 61; p. 125 n. 3.

Ronald H. Fritze & William B. Robinson, eds. Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England 1272-1485 (Wesport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press 2002) p. 139.

Christopher Hare. Dante the Wayfarer (New York: Charles Scribner & Sons 1905) p. 3.

Martin Andrew Sharp Hume. Spain: Its Greatness and Decay (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press 1899) p. 13

Philip Jones. The Italian City-State: From Commune to Signoria (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press 1997) p. 381.

Michael Roth. Crime and Punishment: A History of the Criminal Justice System (Belmont, California: Wadsworth, 2011) pp. 64, 66.

Craig D. Uchida, History of American Policing, in Jack R. Greene, ed.. Encyclopedia of Police Science, vo1. 1 (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2007) p. 617.

I understand there were penalties for failing to participate, but were there any rewards for participating? (Aside from taking a criminal off the street.)

Did the townsfolk grab pitchforks and torches like in the movies?

Did the thief usually survive his capture?

I don’t know about the rewards or pitchforks, but there is a penalty for not participating. The thief went to court!

[…] the tower keeper have any crime-prevention functions? If someone raised the hue and cry, for instance, would the tower keeper look for the fleeing criminal from above and let the town […]