The lives of our forefathers send ripples through the generations, shaping who we are today. If one of those forefathers happened to be a U.S. President, he shaped both national and familial history. And if that forefather was assassinated in office, his surviving family carried an extra burden of grief and shock.

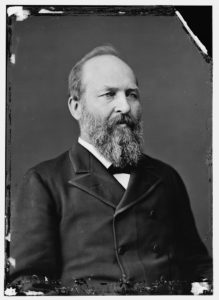

Four U.S. Presidents were assassinated: Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, and John F. Kennedy. Of those, only two – James Garfield and John F. Kennedy – have living descendants today. Hank Garfield, a descendant of President Garfield, joins us today to talk about his forefather, family legacy, and life today.

Charles Guiteau, a disappointed office-seeker, shot and injured President Garfield at a Washington, D.C. train station on July 2, 1881. He died several weeks later, on September 19, as a result of his injuries. In a previous blog post, I interviewed author Fred Rosen, an author of a new book about the Garfield assassination. Rosen claims Garfield’s physician, Dr. Bliss, deliberately killed Garfield, committing second-degree murder, and that Alexander Graham Bell preserved the clues. Hank Garfield wrote the foreword to Rosen’s book.

Hank, you are a descendant of President Garfield. Just how are you related to him?

I’m the great-great-grandson of the president. He had four sons, and they all had sons, and so forth, so there are a lot of Garfields running loose in the USA.

Did the assassination still affect your family several generations later? If so, how?

I don’t know that the assassination affected my family at all within my lifetime. It’s an interesting conversation starter, but it also leaves people with the misguided impression that we have Kennedy-esque connections and wealth, which we don’t.

You actually got to meet one of the Kennedys at school. What was that like? Did you ever talk about either family’s history?

That would be Michael Kennedy, RFK’s son. We were in the same class at St. Paul’s in Concord, New Hampshire. He was small, athletic, charming, and much more worldly than I was. Our circles of friends overlapped a little. We played backgammon and had a conversation that went along the lines of “You’ve got the Garfield chin, and I’ve got the Kennedy nose.” We both liked the TV show Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Some Secret Service agents came to school and followed him around for a couple of weeks when there was a threat against the family. He was killed in a skiing accident when he was about forty. I remember seeing it on the news in California.

Note: The Kennedy Hank Garfield means was Michael LeMoyne Kennedy (1958-1997). He died went he hit a tree while playing football on skis on December 31, 1997 in Aspen, Colorado.

Did your family have any stories or memorabilia about President Garfield?

I honestly can’t remember any. I have a silver cup that Lucretia Garfield (the President’s widow) gave to my grandfather in 1903, when he was a boy. Their names are inscribed on it. I’m not sure how it came to be in my possession.

You are an author. What kind of books do you write?

I’ve published five novels under the name Henry Garfield but am now writing as Hank Garfield. I’m shopping a long novel called A Sprauling Family Saga, which is what it is, and I also write baseball science fiction.

Does your family history have an influence on your writing?

I guess I like to write with large ensemble casts; perhaps growing up with a large extended family had something to do with that.

In your foreword for Fred Rosen’s book, you state that President Garfield was one of the few scholars to occupy the White House. On what do you base that?

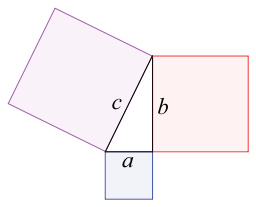

There’s a persistent legend that he could write Greek with one hand and Latin with the other. I’m not sure I believe this. But his mother put great stock in education, believing it was the way for him to escape the poverty of living in a fatherless household on the Ohio frontier (His father died when he was very young). He is also credited with an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem. He seems to have had a curious mind that moved in many directions. Most true scholars exhibit this kind of interest in a broad range of subjects. They used to be called Renaissance men, an allusion to Da Vinci, I guess.

Might the Garfield legacy have inspired you to write?

I grew up in a household full of books. A couple of them were about my great-great grandfather. His son Harry (my great-grandfather) became president of Williams College, the President’s alma mater. My parents were teachers and readers. In the summer we lived without TV. I was always encouraged to read. That, above everything else, inspired me to write.

What do you do now?

I write novels and teach creative writing at the University of Maine. Lately I’ve been working in the genre of baseball science fiction. I also write a weekly blog called Slower Traffic (slowertraffic.net) about living without a car in a rural state. I haven’t owned a car in ten years. It’s the only New Year’s resolution I’ve ever kept.

One of your books, The Lost Voyage of John Cabot, is a historical novel. What inspired you to write about the Age of Exploration?

Well, I love books, and I love boats. My father had a small schooner. I don’t remember not knowing my way around a small sailboat. Today I own a 25-foot sloop and a couple of dinghies. I’m fascinated by the lasting legacy of that time: why the Brazilians speak Portuguese and the Quebeckers speak French, but some Portuguese words creep into Canadian French because of the interactions between New World explorers. In 1983 I was working for a game company in California, and we were looking for mysteries in different genres that we could make into game scripts. John Cabot disappeared on his second voyage to America. I wrote a script in which the player sets out to search for him. The company went under before it could be produced, but it was a great starting point for a book.

Note: John Cabot (c. 1450-1500) was a Venetian explorer who sailed to mainland North American in 1497. Historians consider him to be the first European to visit the North American mainland since the Norse settlement of Vinland.

Do any of your other books touch on crime?

My first novel, Moondog, is a classic whodunit, in which a Holmes and Watson team lead the reader on a search for a murderer. Only the murderer is a werewolf. But the structure is basic: a series of murders that the reader is invited to solve along with the protagonist. From a review by Gahan Wilson, the New Yorker cartoonist: “[Moondog] moves along in the classic pattern and follows the rules; the twist Garfield’s given to it is to have the action take place in convincing Steinbeck country amidst Steinbeckian folk, all of whom are quite well-realized and true to the master’s leanings.” Obviously I was flattered by the comparison, as I was by the mention of Carl Hiaasen in a review of the sequel, Room 13. They are two of my favorite writers.

Thanks, Hank Garfield, for joining us!