It was dark.

The clocks on Manchester’s towers were ticking towards midnight on August 1, 1876 when one of the most sensational crimes of Victorian England occurred. A gibbous moon was setting in the west, but you probably wouldn’t have seen it. The night was clouded and trees overhung the lane as 21-year-old Constable Cock picked his way along his beat.

Heading north on Manchester Road in the village of Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Constable Cock overtook a law student, John Massey Simpson, who was heading home. They walked together for awhile. At the intersection of West Point, another policeman, Constable Beanland joined them for a brief chat before Simpson started east along Upper Chorlton Road. He only walked about 150 yards when two shots rang out behind him, following a man’s voice: “Murder, murder! Oh, I’m shot!”

Simpson ran back to find Constable Cock on the ground, blood spurting from his chest, and Beanland standing over him, blowing his whistle to alert other policemen on their beats. Nicholas Cock died before he had a chance to say who killed him.

Thus began one of England’s most spectacular murder cases – famous not only for the cold-blooded killing of a police officer, but for a Perry Mason-like twist that later turned the entire case on its head. Constable Cock has never been forgotten in England. Even today, police officers on

Constable Cock has never been forgotten in England. Even today, police officers on beat in Chorlton-cum-Hardy stop by his grave to pay their respects.

An American Civil War connection

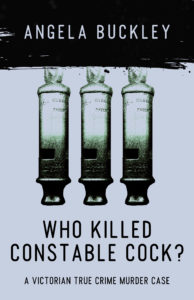

Angela Buckley has just published a book on the Constable Cock case, the second in her Victorian Supersleuth series. I won’t give away the twist – it would spoil the book for you – but can say that one of the surprising aspects for me was the connection to the American Civil War.

Buckley’s book covers two sensational Victorian crimes because one influenced the other. A murder in the Fenian Rising nine years before Constable Cock’s murder changed public sentiment. And that influenced the Constable Cock Case. Instrumental in the Fenian Rising and the murder were two Civil War veterans, Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy, who returned to Europe after the war.

Angela Buckley joins us today to talk about the connection between the two cases.

Welcome, Angela!

Colonel Thomas Kelly and Captain Timothy Deasy were both American Civil War veterans, yet they sparked one of the most sensational criminal trials of Victorian Britain. How did that come about?

Following the American Civil War, many members of Irish Republican Brotherhood (also known as the Fenians) returned to their homeland to continue the battle against the British authorities for home rule. Veteran Colonel Thomas J. Kelly was instrumental in planning the Fenian Rising of 1867. When the campaign failed, Colonel Kelly was arrested but later escaped.

Later that year, Kelly was re-arrested in Manchester, along with one of his colleagues, Captain Timothy Deasy. On 18 September, the prisoners were being transported to prison when the police van was attacked by their supporters. Kelly and Deasy were liberated but only after a police officer Sergeant Charles Brett had been shot dead. A massive manhunt followed, which led to the arrest of some 50 Irish men in the city. On 23 November 1867, William Allen, Michael Larkin and Michael O’Brien were hanged for Sergeant Brett’s murder and became known as ‘The Manchester Martyrs’. Colonel Kelly and Captain Deasy fled back to the US.

Were they ever tried themselves?

No, Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy were never re-captured and both took refuge in the US. Colonel Kelly remained a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in New York and died in the city in 1908. He is buried with his wife in Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx.

What kind of a career did the two have in the Civil War?

Timothy Deasy had migrated from Ireland to America with his family in 1847. In 1861, he enlisted in the 9th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, primarily made up of Irish-Americans. He fought in 32 engagements showing considerable gallantry and leadership. Despite being wounded in the Battle of Spotsylvania, Deasy remained in command of his company. At the end of Civil war, he became a captain in the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Thomas Kelly was also a ‘battle-hardened’ veteran of the Civil War. He had emigrated to the US from Ireland in 1851. During the Civil War he served in the 10th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, also an Irish regiment. He was promoted to First Sergeant of C Company in the summer of 1861. Like Deasy, Kelly was badly wounded but continued his service. He attained the rank of captain.

How did these two Civil War veterans influence prejudice against the Irish?

The nationalist fervour of both these men was renewed during the American Civil War and, in 1865, they were ready to take arms against the British authorities. This led to a more organised campaign with greater structure and focus. Colonel Kelly took charge of Fenian operations in Manchester and Captain Deasy was stationed in Liverpool. Terror of Irish nationalism and the Fenians was already rife in mainland Britain, and this new campaign sent Victorians of all levels of society into an acute panic, reinforcing their long-held prejudice against the Irish in general.

Your book is about the murder of a Victorian police officer that was sensationalist in its own right. Nevertheless, Kelly’s and Deasy’s actions had a huge influence on the Constable Cock case. How?

Although the murder of Constable Cock took place almost a decade after that of Sergeant Brett, the Fenian uprising in Manchester was still fresh in the minds of the city’s inhabitants. As the prime suspects were three Irish brothers, known locally for their drinking and belligerence, their case was seriously prejudiced by contemporary opinions, despite there being no real proof for such assumptions and only the flimsiest of evidence against them. Furthermore, at that time in Manchester, 25 per cent of convicted criminals were Irish and a third of prisoners in its principal gaol were Catholic. At the Habron brothers’ trial, most of the witnesses for the defence were illiterate Irish co-workers, whose testimonies were discounted.

A critical piece of evidence in the Constable Cock case dealt with footprint evidence. How advanced were footprint comparisons as a forensic tool in 1876?

By 1876, the identification of suspects through footprint analysis was a fairly common practice used by the British police. However, the methods were still very rudimentary. In this case, the investigating officer, Superintendent James Bent, made impressions with the suspects’ boots next to the footprints near the crime scene and then compared the two – he even had to cover the prints with a cardboard box to preserve them when it started to rain! Despite the absence of any scientific analysis, Superintendent Bent was satisfied that the prints near the spot where Constable Cock was murdered had been made by his prime suspect William Habron. The boot prints were the main evidence on which Habron was tried for murder.

_______________________________________________________

Thank you, Angela!

Read Angela’s book, Who Killed Constable Cock, to get a completely different view of the evidence.

Literature on point:

Moonrise, Moonset, and Phase Calendar for London, August 1876

Angela Buckley, Who Killed Constable Cock?: A Victorian True Crime Murder Case (Manor Vale Associates, 2017)