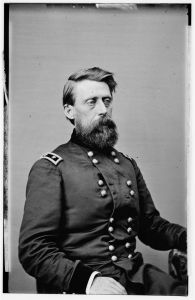

Part Two: The Offender, Jefferson C. Davis

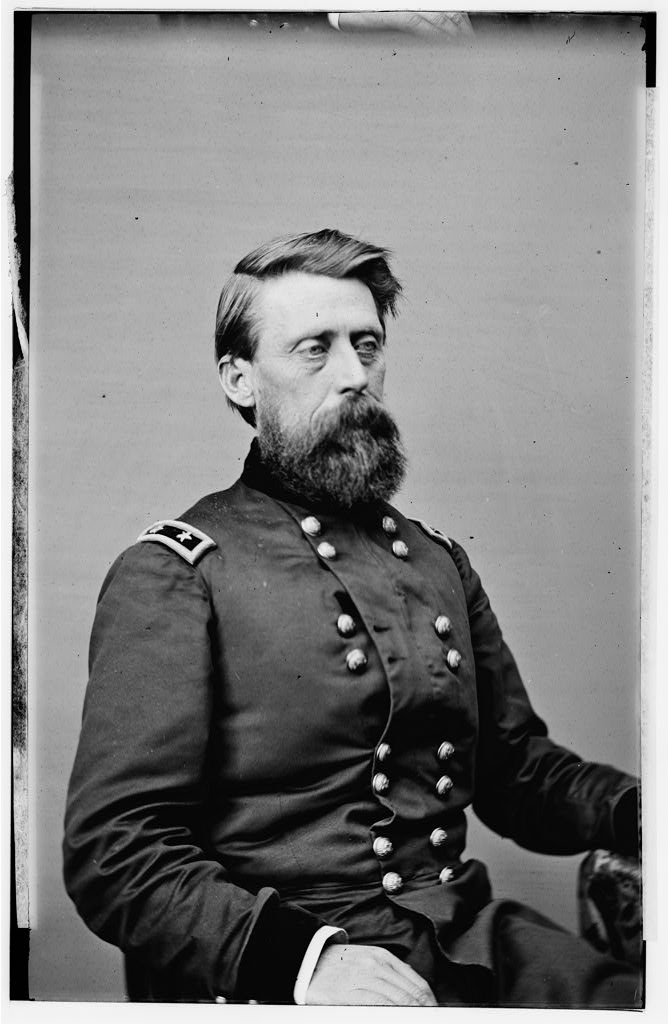

It was a shot that echoed through Civil War history, but not through the corridor separating North and South. When one Union General, Jefferson C. Davis, aimed a pistol at another Union General, William “Bull” Nelson, and pulled the trigger, the act left historians scrambling for answers for decades to come. How could friction between two officers lead to such violence? And why wasn’t Jefferson C. Davis prosecuted?

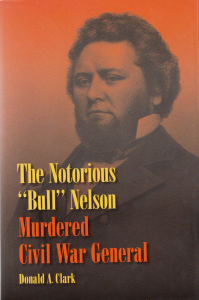

Donald A. Clark recently authored the first biography of Bull Nelson. Last week’s blog looked at Nelson’s personality. Today Don will answer my questions about the perpetrator. If you have any questions for Don, feel free to post them in the comment section.

How did the murder happen?

On Wednesday September 17, 1862 it appeared certain that Confederate forces were about to attack Louisville when Nelson resumed command of the badly demoralized Army of Kentucky. Days later, Union Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis reported to Nelson and he was ordered to organize a motley group of volunteers into a Home Guard Brigade. Word got around that Davis loathed the assignment and gossiped endlessly about Nelson. On Monday September 22, 1862 Nelson called Davis into his office and asked for an accounting. Davis used “about” in place of specific answers, and that led to an obnoxious confrontation with Nelson who ordered Davis to leave the city and report to the commander at Cincinnati.

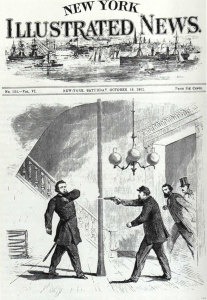

Davis returned to Louisville on Saturday, September 27, 1862 and he made no effort to report to Major General Don Carlos Buell or Nelson. About 8:00 a.m. Monday, September 29, Davis was “in shirtsleeves, without a hat, and greatly agitated” when he confronted the similarly attired Nelson in the lobby of the Galt House Hotel. The five foot seven inch Davis weighed about 120-25 pounds and he brashly demanded that the burly Nelson apologize for the manner in which he relieved him of duty. Nelson refused and Davis flipped a waded calling card into his face. Nelson slapped Davis on the side of face with the back of his hand, called him a coward, and headed back up the stairway.

The rough-edged Davis came from an agrarian background that still embraced a deeply complex code of honor that called for the defense of one’s standing among peers. He also knew a court could not restore a demeaned position, but the shedding of blood might accomplish that end. Davis went over to lawyer Thomas W. Gibson and that old friend from the Mexican War loaned him a pistol. During that brief interlude, Nelson returned to the top the short stairway leading down into the lobby. Davis rushed over to the landing and told Nelson to prepare himself. In the next instant Davis shot the unarmed Nelson in the heart. The mortally wounded Nelson staggered back, climbed to the second floor, and collapsed. He was pronounced dead 8:30 a.m. Davis was under arrest in his room on the 4th floor.

Who was Jefferson C. Davis?

As a 19-year old, Jef (his preferred name) Davis served the Mexican War and was promoted to sergeant. His gallant actions at Buena Vista led to receiving a commission as a second lieutenant of artillery in the regular army in June 1848. Davis was a first lieutenant at the surrender of Fort Sumter in 1861 and in August of that year he commanded the Twenty-second Regiment of Indiana Volunteer Infantry as a colonel. Davis subsequently commanded a division as a brigadier general.

Staff officers under Davis admired his nerve and the enlisted men either feared or admired him for killing “Bull” Nelson. Jefferson C. Davis died of pneumonia in 1879 having never attained rank of major general of volunteers, a position he dearly coveted.

How did he get away with a homicide committed in front of witnesses?

On the way to the Battle of Perryville, Major General Don Carlos Buell, Commander of the Army of the Ohio, asked General of the Army Henry Halleck to see that Davis was “immediately” tried by the courts or sent before a military commission. Two staunch supporters of Nelson were killed at Perryville, Buell was subsequently relieved of command, and no one had the courage to take up the cause of a tyrant that was being severely ridiculed by the press.

General Horatio Wright released Davis from close arrest on October 13, 1862. Wright then concluded that the killing had been done in self-defense and he inexplicably dismissed the matter because he had received no specifications and charges against Davis. On Tuesday, October 21, 1862, it was reported: “Gen. Jeff. C. Davis, who killed Gen. Nelson, has been released from arrest, and ordered to report for duty at Cincinnati.” Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase wrote President Abraham Lincoln on Thursday, October 23, 1862, “Under no circumstances . . . can . . . the killing of one officer by another, —be passed over without the arrest and trial of the offender.”

The press had already drawn one great lesson from this affair. There was an enormous public hatred for military tyrants and that animosity far outweighed the influence of those who supported them. The fourth estate was also buoyed by the belief that President Lincoln would not push for a military court martial because that would go against public opinion. On Monday, October 27, 1862, the Jefferson County Grand Jury in Louisville issued an indictment for manslaughter. Davis was released on $5,000 bond, and on Wednesday, October 29, Special Orders No. 90 called for him to join the newly formed Army of the Cumberland as a division commander. The manslaughter indictment went on and off the docket until May 1864 when it was stricken with leave to reinstate.

Did dueling and its associated sense of honor contribute to the failure to prosecute the case?

The press corps was composed of men who were sympathetic to the outlawed Code Duello and those men had a huge role in making it seem Davis “had to do it.” In St. Louis, the Evening Bulletin rudely declared: “Opinion of the Press on Gen. Nelson’s Homicide —’Served him Right.’“ In New York, the World very wrongly informed its audience that Nelson was a tyrant who had “no friends to mourn” him; and his passing “can barely atone for the wrong and injury he has inflicted.” The Indianapolis Journal told readers the basis for the fatal difficulty with Davis came from “language that no decent man will use to a dog.” Davis told a friend that as a member of “the regular army . . . not to resent an insult of that kind would make me . . . be as the dog that sleeps under my father’s floor.” As aide to Governor Oliver P. Morton stated it Davis had done nothing he “would have deserved to be shot himself.” It is no wonder that at the turn of the century the Boston Globe used that mindset in telling readers “the virtue of civil institutions” should not be judged by the indifference given to this particular aberration because “Public opinion in Kentucky recognized such encounters between gentlemen and officers as affairs of honor.”

The New York Times said the crime of murder requires a “swift and relentless penalty” and it was deeply regretted that Nelson’s “rude and offensive personal deportment” will in all likelihood “exempt . . . his killing from the usual regrets and sympathies.” The Cincinnati Times believed that Davis was justified and the editorial wrongly characterized Nelson an unqualified tyrant who had contributed nothing to the war effort. That paper (and others) reflected the feelings of a people who were out of patience with a poorly executed war effort. That paper believed “military power must be exercised in the same spirit as the principals upon which our government is based . . . . people . . . will not allow themselves to be subjected to the ways of a despotic power. When a citizen of the United States becomes a soldier, he willingly surrenders some of that freedom . . . . but by no means does it make him a mere dog in the hands of superiors . . . . Under civil law, an intelligent and honorable judge would agree that the shooting was reasonable under the circumstances. However, if the final military decree should prove different, it will not overcome public sentiment for a man who was wrongly pushed beyond his endurance.”

General James B. Fry addressed a different perspective in stating the “cruel customs” of military service did not justify the action taken by Davis because soldiers “are not only protected by the civil code, but the more stringent military code, to which they are pledged by the oath of office, and by duty to their country.” The influence of Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton was very significant and Buell believed the “fine Italian hand of Morton” sowed “seeds of mischief “that undermined the “authority of the general government.” The Lincoln administration yielded to political expediency and that enabled the unrepentant Davis to live his life as if he was exempt “from the usual regrets and sympathies” that come with taking the life of another.

The unmarried Nelson was survived by two brothers and a sister and the long discarded practice of “blood money” could not atone for the crime.

Section 228 of the outdated 1891 Constitution of Kentucky remains a great embarrassment, because it still requires that officials swear or affirm that “I being a citizen of the state, have not fought a duel with deadly weapons within the State or nor out of it, nor have I sent or accepted a challenge to fight a duel with deadly weapons, nor have I acted as a second in carrying a challenge nor aided or assisted any person thus offending, so help me God.”

Duels among United States Army and Navy officers were not uncommon in the 1840s and military homicides in the Civil War were likewise a problem. Some of the better known are:

1862 Davis murdered Nelson without being called to answer for the crime.

1862 Davis murdered Nelson without being called to answer for the crime.

1863 Dr. George Peters murdered Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn and he was eventually exonerated.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest shot and killed Lt. Andrew W. Gould in a running gun battle and nothing was done.

Lt. Col. William D. Bowen shot and killed Col. Florence M. Cornyn during a court recess and he was exonerated at his own court-martial because Cornyn was perceived in much the same way as Nelson. (I did an article on this)

Confederate Maj. Gen. John S. Marmaduke killed Maj. Gen. Lucius M. Walker in a duel.

Thanks, Don!

Literature on point:

Donald A. Clark, The Notorious “Bull” Nelson: Murdered Civil War General (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press 2011).

I wonder if there are modern occurrences of killings like these during more recent wars – with the basic idea being “There’s a war going on – we don’t have the time or energy for a distracting trial – get back to the battle.”

Hi Brian,

To the best of my knowledge, the American military has never experienced anything like the Nelson/Davis affair before or after. Shooting, manslaughter, and murder does occur and again to the best of my knowledge it is prosecuted to the fullest extent of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. In Vietnam I had two different experiences the men being shot by their fellow soldiers. I was not pleased with the outcome of either case. The shooters were completely exonerated.

Regards,

Don

I assume the lawyer who provided the pistol also did not face any charges…?

Thomas Weir Gibson posted bond for Davis in the Jefferson County Kentucky Circuit Court Case. The Tranter pistol he loaned Davis was returned to him after the shooting and a descendant now has it.

Very interesting. Thanks for sharing Ann Marie and Don!!

You’re welcome, and thanks for the feedback, Jami. I enjoy blogging.

this is very inacurate this trash is terrible if you are looking for information DO NOT USE

Now, that’s an interesting perspective, Bob! I could hardly call Donald Clark’s book trash. It was published by a university press and university press books are usually peer-reviewed. It has passed an academic rigor that most books don’t have to go through. I’ll believe Mr. Clark until he is proven otherwise.

WTF?

History is always interesting, and American military history is really amazing!

I agree with you on that! One of the things I try to do when I write a blog is make history intriguing, especially for those not familiar with it. Thanks for commenting.

Very interesting. Jefferson C Davis was my great grandmothers uncle and I have been looking up information in regards to this and other details about his life. All I knew was that his family was rather intimidated of him and we have civil war memorabilia that belonged to him.

Glad you liked it. What kind of Civil War memorabilia do you have? You sure have a fascinating family background.

Well since General Nelson is dead and not available to defend himself you can say whatever you want. Shameful apologetic coward rewrite

No one is blaming General Nelson. And — what would history consist of if we couldn’t right about dead people because they’re no longer being able to say their piece? History consists of piecing facts together without the benefit of getting to question long-dead people.

Whuh?

In my research for my first book, I came across a letter written by Colonel Charles Anderson of the 93rd Ohio, the brother of Maj. Robt Anderson and the subject of my biography. Anderson knew both men intimately. He called the shooting “justified” based on the insults that Nelson had hurled at Davis. Quite an interesting case.

Insults certainly don’t justify murder the in modern legal system, but the dueling mentality that lingered in the 19th century made such cases more common. Any case that isn’t clean cut is more interesting. Thanks for commenting.

Mr. Clark,

I am Lloyd Jackson of Muscle Shoals, AL. and I’m preparing to present a talk to the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Tuscumbia, a town mentioned in your book makes up part of Muscle Shoals. I would like to ask you a few questions in preparation. If you would be kind enough to email me I would appreciate it very much.

Hello Mr. Jackson — I’m the owner of this website, but I have Mr. Clark’s email address. I will contact you per Email for your permission to share your Email address with him. If that doesn’t work, you can try contacting him via his publisher. Good luck with your presentation!

Davis never received promotion to Major General of volunteers, and had to settle for the rank by brevet (Davis was brevetted Maj Gen USV in August 1864). Davis also received a brevet as Brigadier General in the regular Army. After he was mustered out of the volunteers, Davis resumed his career in the Regular Army as Colonel of the 23rd Infantry, and was still a Colonel when he died. After the murder of Brigadier General Canby in 1873, Davis’ Lieutenant Colonel, George Crook was promoted two grades to fill the vacancy.

Thanks for the clarifying information, Rich. I’ll ask Donald Clark to comment.

who did Davis blame for his lack of promotion?

That I can’t answer — it’s been too long since I’ve read anything about Davis. I’ll ask Donald Clark if he can adress your question.

Pretty darn interesting name for a Union general as well. And did you know he was a governor of Alaska as well (territorial)?

https://totallyrandomgarbage.blogspot.com/2023/08/oddly-named-governors-part-i.html

Didn’t know that. That’s interesting. Thanks.

I grew up in the South and lived by the same code that Gen. Davis lived by apparently. I think John Bernard Books said it best; “I won’t be wronged, I won’t be insulted, and I won’t be laid a hand on. I don’t do these things to other people and I require the same from them” Gen. Davis called him out to a fair fight. Instead Nelson called him a coward and slapped him. Nelson brought this on himself.

Shooting Nelson in retaliation was such an excessive response it wouldn’t count as self-defense, but I can see where you are coming from. Davis had to do something to protect his reputation. An officer should treat others with more respect.