Where can you find the greatest number of true crime titles under one roof?

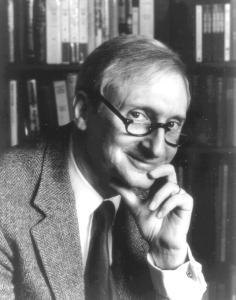

Laura James, attorney and true crime author, recently posted a blog about the Borowitz collection at Kent State University. Albert Borowitz himself published about true crime history. I’ve read some of his work, and his analysis of Friedrich Schiller role in midwifing the birth of the genre in Germany has won my undying recognition. This post originally appeared on Laura’s site “CLEWS: Your Home for Historic True Crime.” Clicking on the permalink below the post will take you directly to her site.

Here’s Laura James:

(The Borowitz Collection is the greatest private true crime library ever amassed. This year the current owner, Kent State University, geared up to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the donation of the entire ensemble. In addition to all kinds of special events, the university put together a catalogue for a special exhibit of the gems of the collection. They asked me to write an introduction for the catalogue, which pleased me to no end, so this is what I came up with to introduce Albert Borowitz and his books.)

* * *

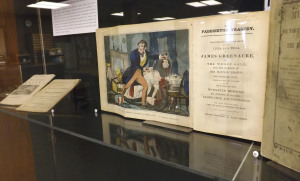

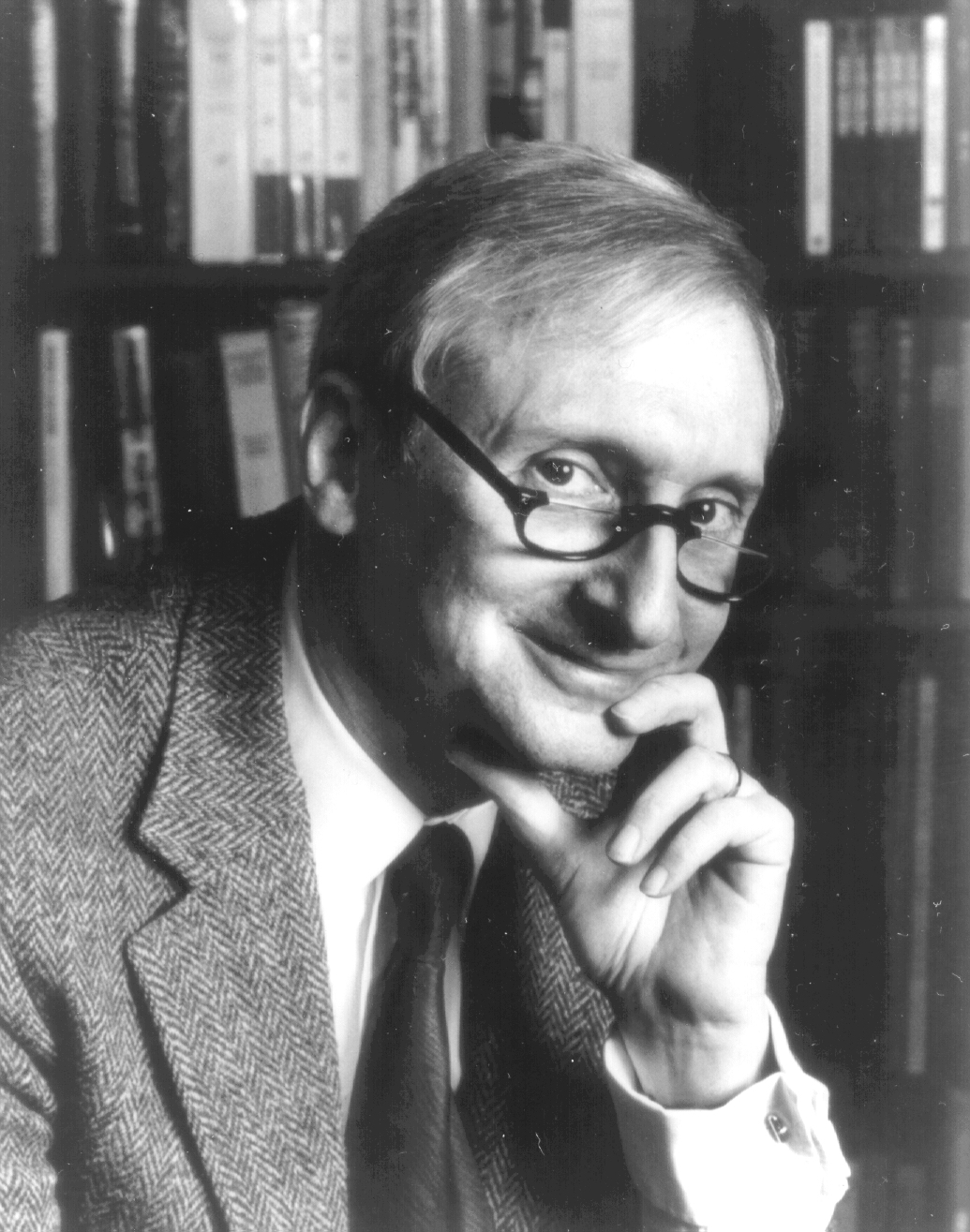

Thanks to the lawmakers and the industry of our criminal courts and mass printers, more or less careful records of murder and mayhem and their aftermath have been kept for ages. But true crime publications tend to be as short-lived as their subjects. Recognizing their value, Albert Borowitz, one of the great true crime historians and connoisseurs of this age, spent decades of his life amassing the largest known private library in the theme, a collection of true crime books exceeding ten thousand volumes, some going back to the 1600s. In doing so, the multilingual American lawyer managed to save generations of stories from several continents, rescuing many books and hundreds of old crime broadsides from extinction, with no other copies left in existence. Now ensconced at Kent State University , it is an awesome trove for researchers and a gift to true crime mavens.

One must envy the energy and passion of anyone who can collect ten thousand of anything, let alone these stories. True crime certainly has its critics. Everyone has personal preferences. And there are fads and poor examples in every genre. But what elevates this particular ensemble is Borowitz’s impeccable taste. There’s not a lot on the professional criminal class (the Mafia, for example) because their motives are simple, brutish, and uninteresting. There’s not all that much on modern serial killers, either (compared to the prodigious output of such stories in the last few decades). Borowitz thinks serial sex killers are “boring.” Now that we have them figured out, we know their motives and patterns of conduct; there is no mystery to examine, no unanswered question left, and Borowitz tells us our time is better spent elsewhere.

The Borowitz collection is also exceptional for its depth of legal scholarship. For it is in essence a law library, part of a long tradition among attorneys and judges of collecting case studies (and handsome books). As thankful members of an organized and lawful society, attorneys in particular are compelled by principles of stare decisis to know the past, which forms our common law. In that sense, studying criminal cases is for some of us a moral and legal imperative. That it can also be an enjoyable process should go without saying.

These true crime stories do more, though. They also feed a common hunger for the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. This ancient oath has been taken over this or that holy book for more than two thousand years. Today, the oath (or affirmation, for secularists) still carries a threat of imprisonment, because the truth is so valuable. Truth means reliability, certainty. And when we get to the truth, we can answer hard questions. Criminal law teems with characters who have been captured, as in amber, by sworn testimony. For the psychologists and sociologists (armchair and otherwise), true cases are rife with answers to the riddles of human conduct and questions of responding to it. Some of us purists even snub fiction and all the figments of crime novelists. Made-up characters and fancied circumstances contrived by a single mind cannot begin to rival the complexity of human conduct. Truth is indeed stranger.

It is often when an elusive truth should be knowable — when the evidence is abundant, the record extensive — that we are most driven to find an answer, and that is reflected in this collection. As true crime fans know, reading one book can draw you more deeply into the literature until you’ve read all there is to read about a particularly mesmerizing matter and you can sit back, sated, and contemplate the question at hand knowing you’ve learned all there is to learn of it. As Borowitz himself has said, “in the study of crime, as in life, the puzzle goes on forever.” We see Borowitz’s research trails in these shelves, share some of his fascinations, and recognize that he has dug deeper and found more in every instance.

Included in his collection are more than 250 volumes on the eternal mystery of Jack the Ripper. Lizzie Borden takes up an entire shelf with more than forty titles to her name. Jesse James has sixty books, going back to 1880. The Praslin murder, a worldwide sensation in 1847, is here represented by twelve extremely rare and quite valuable books in both English and French. Other priceless, one-of-a-kind, historically significant treasures are too many to list.

The collection has continued to grow in a quarter century by acquisition and donation. Beyond the bookshelves are cultural artifacts worthy of the time of scholars as well as the morbidly curious. They include such items as a hangman’s hood, a poison ring, Staffordshire figurines of the murderous Mr. and Mrs. Manning, and the private papers of author Leo Damore, the reporter who broke the story of Chappaquiddick. One can take such things as the sign of a healthy culture; totalitarian states are quick to suppress true crime stories and the paraphernalia that often accompanies them. Those of us who know better celebrate the literature of true crime, which has time and again proven its value those of us who actually recognize and embrace it as the parent of innumerable works of art.

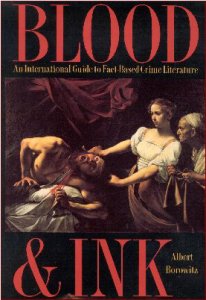

Borowitz will continue to earn accolades from his fellow enthusiasts long into the future not only for his own remarkable achievements in the genre but for his generosity in sharing his collection with the public. To think that a single person acquired all these books, read them all, and indexed them all in Blood & Ink is to know that Albert Borowitz is the legal guardian genius of the genre, and the Borowitz Collection is in and of itself a work of art.

(c) Laura James August 02, 2014; reblogged with permission | Permalink

What is the most written about true crime ever (not just in the Borowitz collection)? and why? (if this is known)

I can’t speak for literature in languages other than English or German, but I suspect the most written-about true crime is the Lincoln assassination. Lincoln’s murder changed the course of American history. Hundreds of books have been written about Lincoln, and no Lincoln biography can avoid addressing the assassination.

The Lincoln assassination fascinated the Germans, too. A lengthy article about it appeared in a prominent German true crime journal as early as 1866.

Does anybody have another suggestion for the most written-about true crime? Please let us know!