My jaw dropped when I first read about it. How did a Sioux medicine man end up on the suspect list? Native Americans must be among the most exotic – and ridiculous – explanations for the series of murders and mutilations that rocked the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. Nevertheless, Black Elk’s name crops up regularly in discussions about the case.

I’ve said before that I’m opened minded when it comes to Jack the Ripper. I don’t favor one suspect over the other. But with Black Elk, I’ll come out and make an exception. It wasn’t him. No way. He had a great alibi, and historical documents back him up.

Although we can rule out Black Elk as a Ripper suspect with a high degree of certainty, the story of how the popular mind connected him with the world’s most famous serial murders is an interesting piece of history in itself.

Here’s the story.

Black Elk as a world traveler

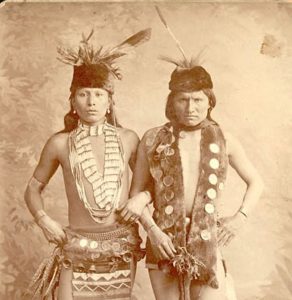

Outside of the crown prince, Black Elk probably has the most name recognition of any Ripper suspect. North Americans acknowledge him as one of the continent’s greatest religious leaders. The Oglala Lakota participated in the battles of Little Big Horn and Wounded Knee and later became a medicine man and holy man. Although he converted to Catholicism in midlife, his biography, Black Elk Speaks, has become a classic of native spiritualism.

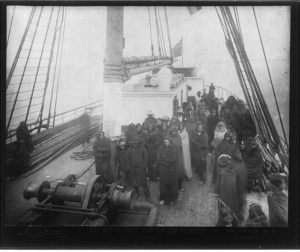

But he was more traveled than you might think. Twenty-four-year-old Black Elk participated in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show in New York during the winter of 1886-1887. When Buffalo Bill continued to Europe in March 1887, Black Elk went with him. He embarked along with cowboys, sharpshooters, musicians, 96 other Native Americans, and Annie Oakley. Buffalo Bill also brought 15 buffalo, 10 elk, 5 head of Texas steer, 150 horses, and a stagecoach.

Black Elk in England

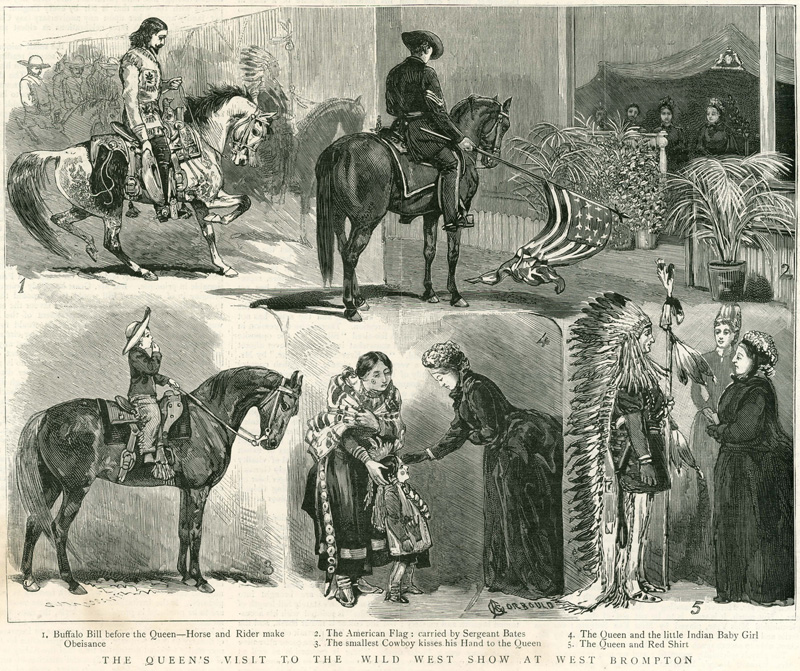

Over the course of the following fourteen months, Buffalo Bill’s troupe performed in London, Birmingham, and Salford (now part of Greater Manchester), playing colorful scenes of the American west. Crowds numbering in the tens of thousands came to watch. Cowboys lassoed steers and rode bucking broncos, Indians danced, erected teepees, and chased buffalo, and Annie Oakley shot a cigar from her husband’s mouth. The tour’s highlight was Queen Victoria. She requested a private performance on May 11, 1887. Black Elk sang and danced for her, and after the show, even shook her hand.

Then personal disaster struck Black Elk. The Wild West show left Manchester by train on May 4, 1888, for one last show in Hull. From there the troupe sailed back to America. But somehow, Black Elk and three other Native Americans got left behind in Manchester.

On to London and France

The four Lakota Sioux left behind spoke only rudimentary English and would have been in a real fix if they hadn’t run into an English-Lakota interpreter. Buffalo Bill’s group had at least two, Bronco Bill and Yellow-Striped Face, but it’s not clear whether this interpreter came from his troupe or a rival’s. One theory is that the interpreter came from a rival troupe and manipulated the Native Americans into missing their train. In a form of human trafficking, he corralled them to the other show group.

The stranded Sioux traveled to London. There the interpreter helped them find reemployment in another, smaller western show, Mexican Joe’s “Western Wilds of America.” Like Buffalo Bill, Mexican Joe performed with cowboys, Indians, and sharpshooters. Black Elk performed at least once with Mexican Joe before the troupe continued to Paris on June 13, 1888.

Black Elk arrested and interrogated

A policeman arrested and interrogated Black Elk and his companions on their third day in London. He wanted an account of their whereabouts and later let the group go. Black Elk assumed the police blamed them for something that had happened but he never specified, any maybe never even learned, what it was. Some people have speculated that interrogation was part of the Ripper investigation, but as you’ll see below, the timing is all wrong.

When Mexican Joe’s troupe opened in Paris around June 15, 1888, Black Elk was with him. Mexican Joe then toured Belgium, returning to England sometime that autumn. Half a year later, around April 1888, Black Elk fell ill and Mexican Joe dropped him from the troupe’s roster. Buffalo Bill, however, returned to Europe for another tour in May 1889. When Black Elk heard about it, he traveled to Paris. There Buffalo Bill brought him a return ticket and sent him home. Black Elk arrived in New York on June 17, 1889, and from traveled back to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre, just 18 months later.

Why Black Elk as a Ripper suspect?

Jack the Ripper terrorized London in the late summer and fall of 1888. He killed at least five victims on August 31, September 8, September 30 (two murders), and November 9. All but one victim was mutilated. Englishmen had trouble believing one of their own could commit such an act and their thoughts turned to the mutilations they’d heard about from the American West. Following the second murder, one newspaper drew an analogy to the recent Wild West performances: the murderer was a ghoul who stalked down his victims like a Pawnee Indian.

Apparently, letters to the editor followed, reporting the stranded Indians from Buffalo Bill’s show. Rumor had it that the Indians were still in London’s East End. They might have been angry about getting stranded and started taking it out on the English.

The Native Americans’ dubious connection to the Ripper case anchored itself in the public imagination. Black Elk, Buffalo Bill, and Mexican Joe feature in a cartoon and film about the Ripper, both called From Hell. Fear and prejudice may have played a role the finger pointing, but to be fair, I should point out that the police also investigated two of Mexican Joe’s cowboys.

An airtight alibi

And so, as the rumor went, Buffalo Bill’s stranding four Native Americans in Manchester put them in the right place at the right time – in England during the Ripper murders. But it’s not as easy as that. If you track down Mexican Joe’s performance schedule, you’ll see that for all but two of the murders, Black Elk has an alibi as waterproof as a birchbark canoe.

Mexican Joe is harder to track than Buffalo Bill because he tended to advertise with posters, not newspaper ads. Nevertheless, Tom F. Cunningham of the English Westerners’ Society has done an excellent job reconstructing Mexican Joe’s performance schedule through newspaper reviews of his shows. Mexican Joe opened in Paris in June 1888 and then traveled to Belgium to open there in August. He remained there until at least September 21. By October 8, he was probably back in England, because a British paper identified two of his cowboys as Ripper suspects. On October 13, he opened a show in Birmingham, and by November 9, was in Sheffield.

The only time for which Cunningham could not account for Mexican Joe’s location was the period between September 21 and October 13. Two Ripper murders occurred on September 30. But if one person was responsible for the canonical five murders, it couldn’t have been Black Elk. He wasn’t even in the country for the first two, and for the last, he was in another city. And he had a troupe of hundreds to attest to that.

Even though more murders than the canonical five might be ascribed to Jack the Ripper, I’m not aware of any that happened in May 1888, when Black Elk was arrested, interrogated, and released in London. Whatever crime that policeman was investigating, it wasn’t the Ripper killings: officially, they hadn’t started yet. Finding the file for that investigation would make an interesting research project — if anyone in London wants to take it up.

I won’t usually say this about any other suspect, but I will for this one. We can rule out Black Elk as a Ripper suspect. The Oglala Lakota holy man didn’t do it.

Who do you think was the craziest Ripper suspect ever?

Literature on point:

Peter Carlson, Encounter: Buffalo Bill at Queen Victoria’s Command, American History Magazine, Sept. 29, 2015.

Tom F. Cunningham, Black Elk, Mexican Joe & Buffalo Bill: The Real Story (London: The English Westerners’ Society, 2015).

Raymond J. DeMallie, ed. The Sixth Grandfather – Black Elk’s Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt (Lincoln: Univesity of Nebraska Press, 1985).

John G. Neihardt, Black Elk Speaks (William Morrow & Company, 1932).

Souvenir Album of the visit of Her Majesty Queen Victoria to the American Exhibition (1887).

Michael F. Steltenkamp, Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Missionary, Mystic (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993).

“The Queen at the Show: Victoria Attends Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Circus,” Washington Post, May 13, 1887.

This reminds me of the awful stories of Jews who were persecuted on the most pitiful of pretexts.

This story shocked me too, Susan. It was all too easy for Englishmen to believe none of them could have done it and push the blame on others. I keep telling myself this wasn’t just an anti-Native American thing because some of the cowboys tell under suspicion too. Buffalo Bill’s extravaganza showed England America’s wild side, and that’s what England thought of when the Ripper murders started a few months later. Thanks for commenting!

This is very interesting. I have read quite a lot on Jack the Ripper, but have never heard this theory. I have to agree he is not a suspect. I read one theory about a man in mental institution, put in after murders. Don’t remember his name. He came to New York were there were a few very similar murders. After awhile he went back to England and turned himself in. Another theory.

Thanks for commenting, Stephanie. I was surprised too when I first read about Black Elk as a Ripper suspect. Granted, nobody seriously considers that theory today, but the story of how he came to be a suspect is an interesting window into the past.

Fascinating, Ann! I had no idea. Very interesting.

I didn’t know about it before either, Colleen, so I just had to blog about it.

The Ripper committed his crimes in a densely populated urban slum and continued to evade detection even after the newspapers began to print sensational stories about “Jack the Ripper” that put the whole population on alert. To do this he must have known the layout of the streets and the habits of the local people extremely well, and he must have had an entirely unremarkable appearance that didn’t attract any attention whatsoever.

The suggestion that it could have been someone who was completely unfamiliar with the area, who hardly spoke any English and who would have been seen by the locals as strange and exotic is certainly absurd. Indeed, it should have seemed absurd to any rational person at the time.

Of course, the fact that Whitechapel had such a large and transient population means that the killer might have been someone whose presence in London was never officially recorded, and who was totally unknown to the police of the time and to the authors of all subsequent speculations. It’s one cold case that is never likely to be solved. But there’s no way that Black Elk could ever be a plausible suspect.

I agree wholeheartedly, Andrew. Black Elk never made a plausible suspect. The fact that he has been discussed as a suspect, however, is an interesting window into Victorian society in and of itself. The concept of a serial killer was relatively new, the crimes were horrendous, and the English had trouble believing one of them could do it. It was all too easy to point the finger elsewhere.

Thanks for commenting!

“Mexican Joe” was Colonel Joseph Shelley, who toured with a wild west show that came to Britain in 1887 and in August was part of the Liverpool Royal Jubilee Exhibition. He opened in London on 26 December, 1887. In the early 1890s, his show ceased to be a purely wild west entertainment and in 1894 he appears to have gone bankrupt. By August 1895 he was giving talks on Blackpool sands and was a concert hall entertainer. In October 1897 he advertised an expedition to the Klondyke and apparently vanishes from history.

Thanks so much, Paul, for adding that information about Mexican Joe. Your last sentence about him apparently vanishing from history makes me wonder if there is archival documents about him somewhere out there that historians haven’t discovered yet. Thanks for commenting.

He apparently advertised for 300 men to accompany him, but I didn’t find out whether he ever went or not. I suspected that the ad was a publicity stunt, but it may not have been. There is a biography, but I was not able t obtain a copy at the time I looked at the Black Elk story. Cowboys who stayed on after Buffalo Bill left were questioned, but the only one we know about, of course, is ‘Colorado Charlie’. Sadly, there appear to have been several people with this nickname. I’m pleased that my tit-bit was of interest.

Have you read the book by Tom F. Cunningham, Black Elk, Mexican Joe, and Buffalo Bill: The Real Story (London: The English Westerners’ Society, 2015)? Mexican Joe did indeed travel through Europe with his troupe and Cunningham tracked his movements down through the posters he used to advertise his events. Cunningham put the nail in the coffin of the Black Elk as the Ripper theory precisely because he was able to track down Mexican Joe’s movements.

Great read Ann Marie, really interesting. Could you provide me the source of the arrest of Black Elk in London, please? I have been searching on British Newspaper Archives and Black Elk Speaks, but i was not able to find anything. In Nicholas Black Elk, Michael F. Steltenkamp mentions that incident but he does not provide the source. I would be very grateful if you help me.

From Spain

Hello Jose. It’s been a few years since I’ve written this, so I don’t remember which of the sources I listed discussed the arrest. Skip Hollandsworth’s The Midnight Assassin discusses Black Elk getting detained and questioned in London. Sorry I can’t help you more, but I’d have to re-read the sources and I no longer have access to some of them due to the libraries being closed during the pandemic, etc.

Thank you very much Ann Marie for answering me and for your help. I will take a look at Hollandsworth’s. Thank you again Ann Marie 😉

Good luck!