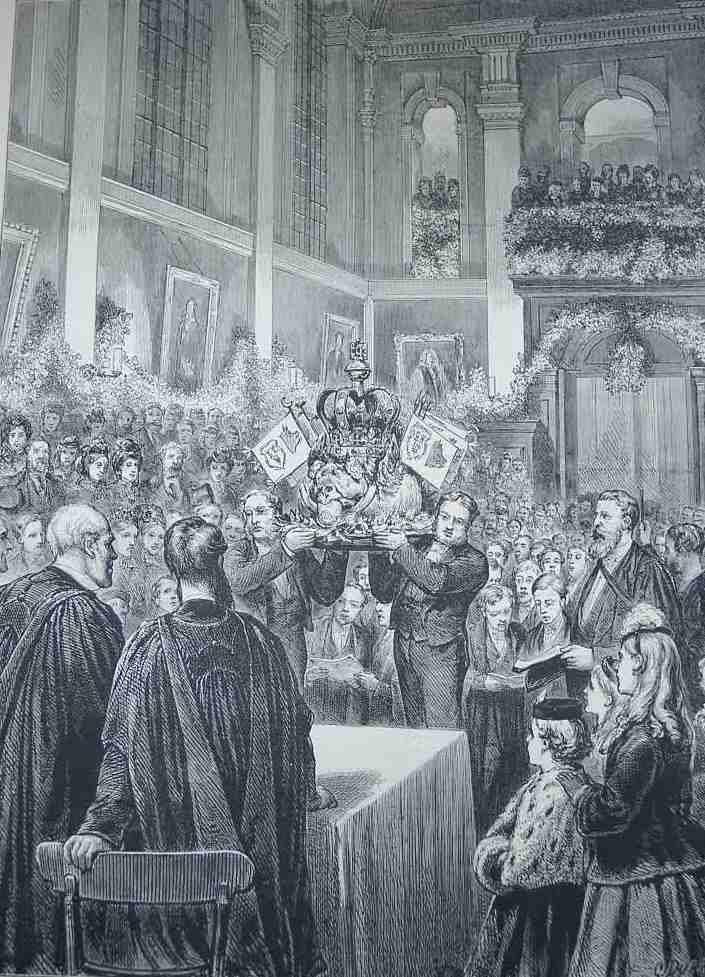

The boar’s head, as I understand

Is the rarest dish in all this land

Which thus bedeck’d with a gay garland

Let us servire cantico.

Thus goes the Boar’s Head Carol, and to explore this traditional Christmas dish, let’s set the dials on our time machine to 13th-century England. Boar’s head featured in the 1289 Christmas menu the Bishop of Hereford. Following the instruction in the online cooking class A Taste of Christmas Past, I took on challenge of filling and roasting one at home. Descriptions of the pig’s cheeks as the best bacon of the entire animal convinced me it could be worth it, despite the reservations of some family members. (“A pig’s head? On the table? Mom!)

The Boar’s Head in England

Not only was the boar’s head a highlight of a medieval Christmas feast, it also has a connection to Queen’s College at the University of Oxford. According to myth, a student was once attacked by a wild boar. He could fight it off and kill it by hitting it with books of Aristotle. This led, apparently, to a traditional Yuletide feast featuring a boar’s head. That explains the carol’s next verse:

Our steward hath provided this

In honor of the King of Bliss;

Which, on this day to be served is

In Reginensi atrio (In the hall of Queen’s).

The recipe for the boar’s head was loosely based on Chiquart’s Du fait de cuisine (1420) and the filling on the Forme of Cury.

My husband went hog wild over this dish. “Who knew the snout had sooo much meat?” he said as he dissected my servings. “It has truffles and saffron!” My sons, who had their initial reservations, dug into the stuffing with gusto.

Wassail

My menu backfired, however, when I served my family wassail, or hot spiced cider. I thought it would be nice to talk to my German husband and sons about the wassailing tradition so they’d better understand the carol, “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” — the exchange of wassail for figgy pudding, and the servants singing Christmas blessings on their master before receiving their holiday treats. (I know January 6 is the traditional date for wassailing, but we are going Mexican that day.)

We looked at the lyrics to the Gloucestershire Wassail (one of my favorite Christmas songs), but when it came to singing it, one of my sons threw up his hands in protest. “I had no idea servants had to beg their masters for food for Christmas!”

“Wassailing was just for fun,” I said. “Of course the masters would have given their servants food for Christmas whether they wassailed or not.”

But he felt like the songs romantized the poverty of the servants. He used to like ‘We Wish You a Merry Christmas,” he said, but decided he doesn’t anymore.

Dang it. Can anyone help me out on the history here to convince him wassailing doesn’t romanticize the downside of servanthood?

Figgy Pudding

Of course I had to finish up with figgy pudding – something the entire family relished.

Metzergei Stollsteimer

Obtaining a pig’s head and having it deboned is not an easy thing, so I want to take a moment to thank my butcher, Thomas Stollsteimer, who not only sourced the pig’s head, but unusual items like venison, wild boar, pig’s blood, and duck for the upcoming recipes.

Tomorrow we’ll explore a little of the Bohemian Christmas culture.

If you’re interested in taking an online class on medieval cooking, check out Eatmedieval.

Merry Christmas!

Have you ever tried a boar’s head before?

Guten Abend, Ann Marie,

sehr interessant!

Ich habe noch nie einen Wildschweinkopf verzehrt.

Der figgy pudding spricht mich mehr an.

Liebe Grüße,

Gabriele

Der Schweinekopf hat besser als erwartet geschmeckt, aber das Gericht war sehr arbeitsintensiv. Deswegen bin ich nicht sicher, ob ich es noch einmal mache. Trotzdem war dieses außergewöhnlich Gericht das perfekte Gegenmittel gegen den Lockdown. Wenn wir nicht reisen dürfen, lassen uns in die Vergangenheit mit mittelalterlicher Kochkunst reisen. Danke für den Kommentar, Gabriele. Und frohe Weihnachten!