The dangers of time travel

You have to admit you’ve at least thought about it before. What would it be like to fly back in time with a time machine?

What would you want to see? The dinosaurs? The life of Jesus Christ? A historical event you’ve been researching and have lingering questions about?

No matter which trip you select, it would be fraught with danger. The dinosaurs might snack on you. You could get caught in a war. If you plan to visit Renaissance Europe and walk around in your jeans and T-shirt, snapping pictures with your cell phone, you can plan on getting arrested. And in case you get marched into the torture chamber, you probably have no idea what your rights would be.

So just in case you find a time machine in grandpa’s attic and contemplate a trip back a few centuries in time to Europe, you’ll want some advice about the legal system – and your legal rights in the torture chamber.

I’m here to help you.

Judicial torture

First, some basic concepts.

Judicial torture – that means torture as a method of collecting evidence and not as a method of punishment – grew out of the Greek and Roman legal systems. By 1252, Pope Innocent IV approved its use in Roman-canon law. That meant it could be used in church procedures (think Inquisition).

When you set the dials on your time machine, your best country to visit, from a judicial perspective at least, would be England. Of all the European countries, England did not adopt Roman-canon law. Instead, it used a jury. Although the English juries evolved over time from investigating bodies to the modern juries we know today, they avoided the judicial torture of continental Europe. In all probability, the members of your English jury would figure out how to turn on your cell phone and get the fright of their lives. But they couldn’t put you on the rack to find out more about it.

As more modern legal systems began to replace the trial by ordeal in continental Europe, judicial torture found acceptance. In fact, people may have found torture not very different – or even a step up from – the medieval ordeals. Trial by ordeal was an ancient religious-judicial procedure to let God decide the case. It meant subjecting the suspect to a dangerous event, e.g. submersion in water. The court interpreted the suspect’s survival as God’s intervention to prove their innocence. Roman-canon law, then, represented an improvement. It increased your chances of surviving a trial.

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

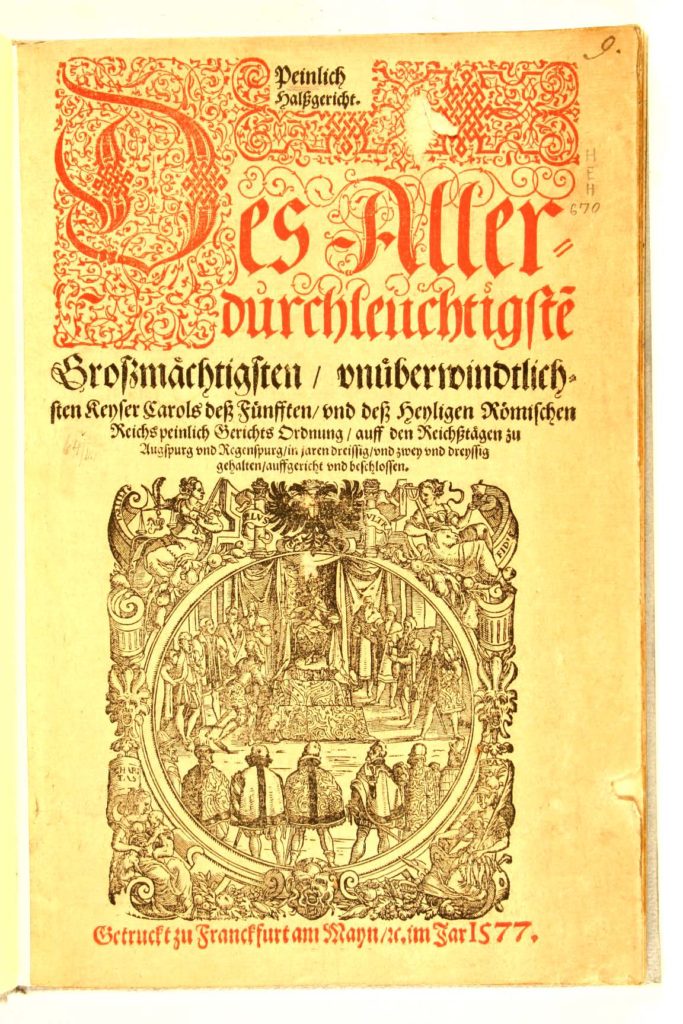

Now set the location dial on your time machine to the Holy Roman Empire and the year to 1532. That’s when Emperor Charles V enacted the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, landmark legislation for criminal law. How is it that this statute, with an awful reputation so often associated with witch trials, actually advanced individual rights?

The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina incorporated many facets of Roman-canon law, but went ever further in balancing the state’s need for an investigation against individual rights. For the first time, a suspect in a criminal investigation had at least some rights against the excesses of the judicial system. The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina also contained some seemingly modern insights – it was the first law to distinguish between first and second-degree murder.

One small stroke from Charles’s pen, one giant leap for individual rights.

By amtliches Werk (Scan from the original work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Your rights under the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

So what would have happened if you started walking around the Holy Roman Empire, snapping pictures, and got arrested? Here’s a small litany of your rights.

No torture without probable cause.

There had to be sufficient suspicion against you before the state could torture you for evidence. A “half-proof” was usually required. That meant half the evidence required to convict you. For example, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina required two eyewitnesses or an eyewitness and a confession as full proof, so one eyewitness who claimed you committed the crime counted as a half proof and counted as probable cause for judicial torture.

No leading questions.

Leading questions in the torture chamber can lead to false confessions. Charles V recognized that as early as 1532. So the Constitution Criminalis Carolina banned leading questions. An interrogator could ask what kind of weapon was used in a murder, but not if it was a knife. He could ask where the body was hidden, not if it had been dumped in the local mill pond. And he could ask what your cell phone is supposed to do, but not if it’s an instrument of witchcraft.

The interrogator tried to elicit information only the perpetrator could know – a technique used today in modern law enforcement to weed out false confessions – and leading questions only got in the way.

Of course, it was difficult to enforce the rule. But many in many cases, the court gave the interrogator written questions ahead of time. And since the Carolina also required witnesses to be present in the torture chamber, it might have been more difficult to get around the prohibition against leading questions than many assume.

Corroboration of a confession.

Even if you did confess, the court couldn’t use that against you without corroboration. Pain might lead a witness to say anything. So if you confessed to something specific only the perpetrator could know, let’s say dumping a body in the local mill pond, the court would require the investigator to check it out.

That’s exactly what happened in a murder-robbery case in Germany’s Rhine Valley in the 18th century. When an accessory to the crime reported that the principals dumped the body in a pond, the investigators were required to dredge it. They couldn’t find the body. Normally, then, there wouldn’t have been enough evidence to convict the accessory. In this case, the court did convict the accessory but based on other evidence.

Compensation if tortured illegally.

Here’s a good one. If you could prove you were examined under torture in violation of the law, you were entitled to compensation. Section 20 allowed you to sue the officials who tortured you illegally. Section 20 also eliminated any defense on the officials’ part based on your having waived your rights.

Safe time traveling

Of course, I hope you’re never subjected to torture and that you enjoy your time travels without any legal entanglements. Despite its advances in individual rights, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina remains abhorrent for its use of torture. Thankfully, Europe abolished torture by the beginning of the 19th century.

The assassination in my book offers some interesting time traveling in this respect. The Kingdom of Württemberg, where the murder took place, abolished torture in 1809. The murder was in 1835. But Württemberg didn’t get around to abolishing the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina until 1843! That means the assassination in my book was one of the last great crimes investigated under the centuries-old law. And it also means that the investigator had to try to prove the case under the old evidentiary system of proof requiring two witnesses or one witness and a confession. Württemberg didn’t recognize circumstantial evidence until 1839 when it adopted a new criminal code.

No wonder, then, that the solution to this case came from America!

You can pick up my book, Death of an Assassin, and enjoy some safe time traveling. And I promise the dinosaurs won’t eat you.

Literature on point:

Clemens-Peter Bösken, Das Ende der grossen rheinischen Räuber- und mörderbande: Der Düsseldorfer Sicehenprozess von 1712 (Erfurt: Sutton Verlag, 2011).

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (partial translation)

John H. Langbein, Prosecuting Crime in the Renaissance: England, Germany, France (Harvard Univ. Press, 1974).

John H. Langbein, Torture and the Law of Proof: Europe and England in the Ancien Régime (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1977).

Wolfgang Schild, “ ‘Von peinlicher Frag’: Die Folter als rechtliches Beweisverfahren,” Schriftreihe des mittelalterlichen Krimminalmusuems Rothenburg o.d.T., Nr. 4 (1999).