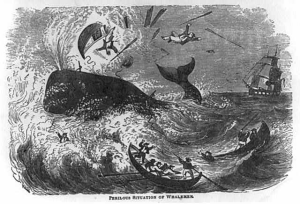

A whale sinks the Essex

Directly towards the ship the sperm whale came, its tail churning the water and its body casting off a wake. As its massive head struck the port side of the Essex, the 87-foot-long whaleship shuddered, oak timbers splintered, and sailors were knocked off their feet.

The sailors thought it might have been revenge. Did the 85-foot-long bull figure out that the source of all those annoying harpoons was not so much the whaleboats, but the mother ship? Scientists today have another explanation. Bull sperm whales make a call that sounds like a pinging hammer, and because the first mate was on board, repairing a whaleboat with a hammer, the whale would have heard those pings through the water. Perhaps it mistook the mother ship for a rival.

At any rate, one frontal attack wasn’t enough for the giant bull. It swam about 500 yards away, turned, and bore down on the Essex’s port bow at full speed. This time when it struck, it was the end of the mother boat. It began flooding.

Inspiration for Moby Dick and a new movie

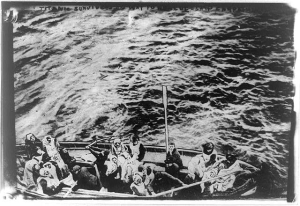

The sinking of the Nantucket whaleship Essex on November 20, 1820 inspired Herman Melville to write Moby Dick. Melville’s story ends with Moby Dick sinking the Pequod, but for the Essex crew, their story began with the sinking. Far out in the Pacific Ocean, 2000 nautical miles west of South America, the sailors had just enough time to pack some provisions and load everyone into three whaleboats. They tried to sail east, but it took 95 days before they were rescued. Of the twenty crew members, only eight survived. And in order to survive, they had to resort to cannibalism. They also drew straws to decide which sailor would sacrifice his life to feed the others.

Drawing straws or casting lots in a lifeboat in this situation was already a long-standing custom of the sea. Even the most naïve deckhand knew what to do in a lifeboat when all the inhabitants were starving, because the sea shanties and ballads memorialized the tradition.

Nathaniel Philbrick wrote an award-winning book about the Essex tragedy called In the Heart of the Sea. It was published in 2000. Warner Brothers will release a movie based on the book in December, 2015. Once the film comes out, the questions will be on everybody’s lips: Is cannibalism legal? And is killing someone who drew the short straw on a lifeboat murder? Or giving one’s life to feed others a noble sacrifice?

One commentator has called the law on cannibalism on the high seas “a perfect storm.” I’ll try to sketch the law in broad brushstrokes, but you better hold tight to the gunwale because there are rough seas ahead.

The Law

Who the heck has jurisdiction?

Is a lifeboat in the middle of the Pacific even subject to any laws? International Law of the Sea regulates navigational issues, giving a Portuguese whaler on starboard tack the right of way over a French passenger ship on port tack, for instance. But international law doesn’t apply to actions on board.

What law applies to a ship’s crew? Some commentators insist a lifeboat on the open sea is a nation unto itself; their isolation from civilization gives the castaways the right to govern themselves. But it isn’t so simple. The framers of the U.S. Constitution thought about that problem and granted federal courts jurisdiction over admiralty and maritime matters in Article III. That includes crimes against U.S. citizens on the high seas.

In short, if a federal court wanted to hear a lifeboat case, it could. But what law should the court apply? Were the sailors’ actions even a crime?

Drawing straws in the lifeboat: the question of consent

Consumption of a human body that has died naturally has never been criminalized, especially in a survival situation. The cases that raise legal issues are those involving deliberately killing another person for food. We can divide those cases into homicides with and without the victim’s consent. In cases involving drawing straws or casting lots, the castaway drawing the short straw agrees to sacrifice his life to save the others.

The history books are rife with accounts of drawing straws in the lifeboat, but I’ve only found one case that resulted in criminal charges. The survivors of the Essex never faced charges. But English sailors adrift in the Caribbean resorted to the practice in 1641 and did have to answer in court. A proctor on the island of St. Christopher pardoned them. He found that the legal doctrine of necessity “washed away” the crime.

Necessity is a legal defense. You can use it to justify or exonerate yourself if committing a crime prevents a greater harm. This doctrine will allow you to run a red light to attract police attention if someone in the backseat is holding a gun to your head; you can trespass on an island or break into a mountain cabin to save yourself in a storm. In this case, one sailor voluntarily sacrificed his life for the survival of the others and the court recognized the killing as an act for the greater good.

But now we need to baton down as we sail into a whirlwind caused by the distinctions between civil and common law.

Common law versus civil law

Roughly speaking, English and American courts use the common law, or case law, in which judicial decisions have legal precedent. Continental Europe uses civil law, based on Roman legal principles, in which statutes are the primary source of law. But there are exceptions. English admiralty law of the early 19th century was based on civil, not common, law.

Civil law, in the case of survival cannibalism, is more lenient than common law. It recognizes necessity as a defense and to an extent, also recognizes customary law. The decision in 1641 was probably based on civil law (the original decision is lost, so scholars cannot say for sure).

But the question came up in the common law in the late 19th century. The English case of Regina v. Dudley and Stephens (1884) is the leading case in common law, and in that case, the English judges ruled that necessity can never be a defense to murder. The judges convicted Dudley and Stephens for killing another castaway for consumption. They sentenced the men to death, but Queen Victoria pardoned them and reduced the sentence.

Regina v. Dudley and Stephens also cited an older American case, U.S. v. Holmes (1842), as precedent. But both Holmes and Dudley and Stephens can be distinguished on the grounds of consent. The castaways never drew straws. Instead, they killed the weakest member without his consent (in the first case) and threw several people overboard without their consent to lighten the load (in the second case).

It may be that the issue of survival cannibalism with the victim’s consent has never been tested in the common law. Today, two changes would tip the scales in favor of the defense. Starving people probably have trouble thinking straight, and courts today are more likely to recognize diminished capacity as a defense. Second, some scholars have theorized that the Dudley and Stephens decision was a judicial reaction again the new theory of Darwinism. They didn’t want to admit that man can be reduced to survival of the fittest. If so, such a backlash is less likely today.

Want to know more?

Michael O’Donnell, in a project for the National University of Ireland School of Law in Galway, produced a video about the Regina v. Dudley and Stephens case. It includes fascinating interviews with a couple of professors. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A03p_egwaSg

I don’t claim to be an expert in admiralty law and invite anyone who can add to the discussion to post a comment!

How would you rule if you were a judge and the Essex case came before your court?

Literature on point:

Nathaniel Philbrick, In the Heart of the Sea (Viking Adult 2000)

A.W. Brian Simpson, Cannibalism and the Common Law (University of Chicago Press 1984)

[follow_me]

I was just about to read Moby Dick… but you spoiled the ending. 🙁

(just kidding)

If “English judges ruled that necessity can never be a defense to murder”, what about did they think of self defense? Isn’t that a a type of necessity?

Self-defense is separate from the defense of necessity and remains a defense to murder in English law. One of the English judges commented that had the victim killed the defendants when they started to slit his throat, it would have been self-defense.

Warner Brothers just pushed the release date back from March to December 2015. At any rate, here’s a link to the trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IdfGWfbNYI

looks like a real nail-biter! (cannibalism joke)

Actually, Brian, I’m wondering how Warner Brothers is going to handle the cannibalism. No one wants to watch that on the big screen. It will probably have to be off screen.

Fascinating!! Love your stuff, Ann.

Thanks, JamiG4! I love writing.

Great post, Ann! I can’t wait for the new movie. Such a gritty story, I’m sure. Had never thought about the legal ramifications before—very interesting.

Thanks, Colleen! This is the movie I’m looking forward to the most for 2015. It’s a piece of history stranger than fiction. Who knows if the movie will go into the legal ramifications?

Fabulous post, Ann! And it brought back fond memories of my first year of law school – we studied Queen v. Dudley and Stephens in criminal law.

Thanks, Mimi! I find it interesting that you studied Queen V. Dudley and Stephens, because at the University of Washington School of Law, we didn’t. But there are always new cases to learn about, and the ones that cut so close to the definitions of murder that the sparks fly are the ones that are the most interesting.

I’m curious: Where did you go to law school?

I went to UC Hastings. Criminal law was the first semester of 1L and the lifeboat cannibal case definitely captured everyone’s interest!

It would! I wish we would have discussed it too. But it probably depended on which casebook the law school used.

Nice job Ann Marie. Deez nutz

Thanks so much for stopping by and commenting!

nice job ann

Thanks a bunch!