It’s perhaps fitting that one of the most controversial hearsay exceptions was first used in one of the most controversial trials of United States history. The muskets the British soldiers fired in the Boston Massacre found their marks in American patriotism. The massacre became a watershed event in American history – one of the events that incited the American Revolution.

A statement defense attorney John Adams introduced into evidence also echoed through the hallways of judicial history. The Boston Massacre trials marked the first time the American history the dying declaration was used as evidence.

What is the dying declaration? Why is it so controversial? And what role did it play in the Boston Massacre?

The dying declaration as a hearsay exception

Hearsay is one of those boundary stones that demarcate the law of evidence. It consists of an out-of-court statement, made by anyone other than a defendant, offered into evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted. Courts exclude hearsay because it isn’t as reliable as court testimony – it isn’t made under oath and isn’t subject to cross-examination. The jury can’t judge the declarant’s demeanor.

But there are lots of exceptions. One of them is called the dying declaration.

Here’s how the Federal Rules of Evidence define the dying declaration. State rules of evidence are similar.

Rule 804. Hearsay Exceptions: Declarant Unavailable

(b) Heasay Exceptions: The following are not excluded by the hearsay rule if the declarant is unavailable as a witness:

….

(2) Statement Under Belief of Impending Death. In a trial for homicide or in a civil action, a statement a statement that the declarant, while believing the declarant’s death to be imminent, made about its cause or circumstances.*

Not a deathbed confession

Note the difference.

A declarant must have made a statement about the cause of what he or she believes to his or her impending death. Some states require that the declarant actually died before allowing the statement into evidence.

Courts consider dying declarations reliable enough to overcome the hearsay rule: A dying person doesn’t have reason to lie, and a statement about the cause of death might be the only evidence available. Think of it as giving the dead a say in court.

When a person clears their conscience on their deathbed, however, and confesses to a crime, law enforcement can use that to help close a case, but it can’t be admitted into evidence.

Shakespeare and the dying declaration

The dying declaration dates all the way back to 1202 – the reign of King John. And that’s perhaps fitting, because Shakespeare includes a dying declaration in his play King John (Act V, scene 4):

Have I not hideous death within my view …

What in the world should make me now deceive,

Since I must lose the use of all deceit?

Why should I then be false, since it is true

That I must die here and live hence by truth?

Dying declaration and the confrontation clause

The possibility that some people might lie on their deathbed makes the dying declaration controversial. In a 2004 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court called many of the traditional hearsay exceptions into question: The lack of opportunity to cross-examine the declarant can violate the confrontation clause of the Constitution. The Court hasn’t specifically addressed the dying declaration, but its future is now in the air.

Dying declaration in the Boston Massacre

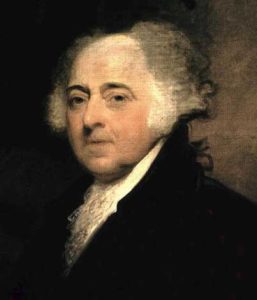

As a 34-year-old lawyer, the future President, John Adams, defended the British soldiers. The job guaranteed unpopularity with the American patriots, but Adams felt it was his ethical duty to offer representation. He did a good job, too. Most of the soldiers were acquitted, and for the other two, Adams could reduce the crime down to manslaughter.

Critical to his defense was the dying declaration of Patrick Carr, one of the victims. This testimony constituted the first use of the dying declaration in the American colonies. In violation of colonial law, two British soldiers had fired on a mob of Americans when the soldiers felt threatened. Carr’s deathbed statement to his doctor goes to the cause of his death and indicates a lack of premeditation – an element of murder.

Here is John Adams in the courtroom, examining the doctor on the stand:

Testimony of Dr. John Jeffries

Q. Was you Patrick Carr’s surgeon?

A. I was in the company of others. I was called that evening about eleven o’clock to him…. Dr. Lloyd, who was present, turned round to me and said Jeffries, I believe this man will be able to tell us how the affair was, we had better ask him: I asked him then how long he had been in King-street when they fired? he said he went from Mr. Field’s when the bells rung, when he got to Walker’s corner, he saw many persons coming from Cornhill, who he was told had been quarrelling with the soldiers down there, that he went with them as far as the stocks, that he stopped there, but they passed on: while he was standing there he saw many things thrown at the Sentry. I asked him if he knew what was thrown? He said he heard the things strike against the guns, and they sounded hard, he believed they were oyster shells and ice; he heard the people huzza every time they heard anything strike that sounded hard: that he then saw some soldiers going down towards the Custom House, that he saw the people pelt them as they went along, after they had got down there, he crossed over towards Warden and Vernon’s shop, in order to see what they would do, that as he was passing he was shot, that he was taken up and carried home to Mr. Field’s by some of his friends. I asked him whether he thought the soldiers would fire; he told me he thought the soldiers would have fired long before. I then asked him whether he thought the soldiers were abused a great deal after they went down there; he said he thought they were. I asked him whether he thought the soldiers would have been hurt if they had not fired; he said he really thought they would, for he heard many voices cry out, kill them. I asked him then, meaning to close all, whether he thought they fired in self-defense, or on purpose to destroy the people; he said he really thought they did fire to defend themselves, that he did not blame the man, whoever he was, that shot him. This conversation was on Wednesday. He always gave the same answers to the same questions every time I visited him.

Q. Was he apprehensive of his danger?

A. He was told of it. He told me … he was a native of Ireland, that he had frequently seen mobs, and soldiers called upon to quell them…he had seen soldiers often fire on the people in Ireland, but had never seen them bear half so much before they fired in his life…

Q: How long did he live after he received his wound?

A. Ten days.

Q. When had you the last conversation with him?

A. About four o’clock in the afternoon, preceding the night on which he died, and he then particularly said, he forgave the man whoever he was that shot him, he was satisfied he had no malice, but fired to defend himself.**

Justice Oliver gave the following instruction to the jury:

This Carr was not upon oath, it is true, but you will determine whether a man, just stepping into eternity, is not to be believed; especially in favor of a a set of men by whom he had lost his life.***

John Adams’s legacy

John Adams later confided to his diary that his representation of the British soldiers was one of the most important things he’d ever done in his life:

The Part I took in Defence of Cptn. Preston and the Soldiers, procured me Anxiety, and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life, and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently. As the Evidence was, the Verdict of the Jury was exactly right.****

You might also like: The Five Greatest Criminal Trials of History. It also goes into the witch trials John Adams so despised.

What do you think? Should dying declarations be allowed as evidence?

Literature on point:

****John Adams, diary, March 5, 1773 (public domain).

Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36 (2004).

*Federal Rules of Evidence.

***Frederic Kidder & John Adams, History of the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770 (Albany, NY: Joel Munsell, 1870).

Liang, B. A. and Liang, A. C., Lies on the Lips: Dying Declarations, Western Legal Bias, and Unreliability as Reported Speech, Law Text Culture , 5, 2000.

Douglas Linder, “The Boston Massacre Trials.” Jurist (July 2001).

**Trial of the British Soldiers (Boston: William Emmons, 1824).