Fanny Workman refused to conform. That refusal developed into what Germans call a “red thread” – the common theme that explained much of her life (1859-1925), and in particular, her record-breaking adventures.

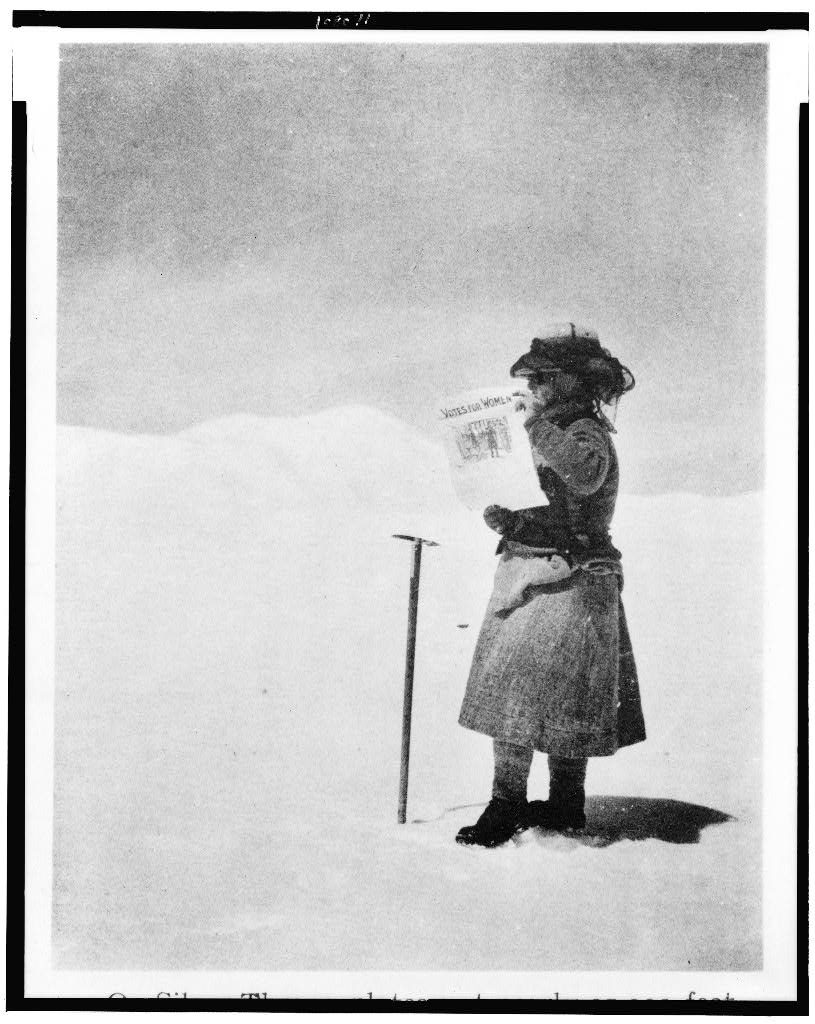

As the daughter of a Massachusetts governor, she eschewed the finishing schools expectations for the young women of the time and took up mountain climbing as a hobby. As U.S. citizen, she refused to conform to the role of an American wife and moved with her husband to Germany. When the couple vacationed, they selected the bicycle as their means of travel and broke several cycling records. But that wasn’t enough. Fanny Workman went on to smash several mountain climbing records – even records held by men. But the scientific community’s refusal to recognize a woman’s accomplishments propelled her into another arena. Fanny Workman became active in the woman’s liberation movement and advocated for women’s suffrage.

Interview with Cathryn J. Prince

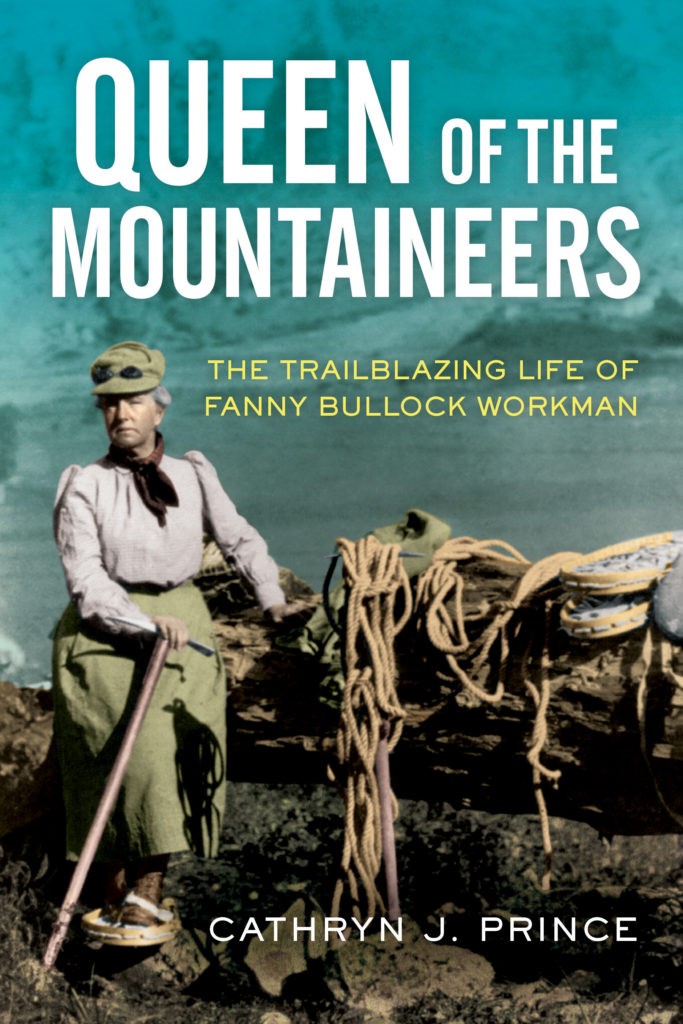

Cathryn J. Prince’s new biography of Fanny Workman, Queen of the Mountaineers: The Trailblazing Life of Fanny Workman, not only rivets the reader with adventure in parts of the world most of us will never visit. It also highlights the strength of one woman’s character – and how she changed the world. Cathryn J. Prince joins us today to talk about the exploits of a German-American worth remembering.

Welcome, Cathryn J. Prince!

What records did Fanny Workman break?

In 1906 when Workman summited Pinnacle Peak at 23,500 feet she set the altitude record for women. Her record remained unbroken until 1934.

She actually broke the record (her own) twice before. She also held the record for bivouacking two consecutive nights above 19,000 feet – during a storm no less. She cycled the length of India from south to north. Additionally, she was the first woman to lecture at the Sorbonne in Paris.

How did she influence the popularity of bicycle road trips in Europe?

After the birth of her second child, Siegfried, Workman decided it was time to try bicycling, which was still new. At first she cycled around the streets near her home in Dresden. Once she felt confident she ventured further out across Germany. She wrote an article, “Bicycle Riding in Germany” for Outing magazine. It highlighted both the virtues of cycling for ones’ health and how cycling was a popular pastime for Germany’s men and was fast becoming popular among women. She described the rules of the road. She also stressed that cycling allowed one no small measure of independence.

In time she and her husband took months long bicycle trips through Germany, Algeria, Morocco, Spain, India and present-day Vietnam. She wrote about each of these adventures. Those books delighted arm chair travelers and encouraged people to embark on their own adventures.

Why did she and her husband choose to live in Germany?

After the deaths of their fathers the couple decided to decamp for Europe. They had become enamored with the continent after spending several holidays hiking in Switzerland and Germany. They relished the idea of indulging their shared tastes in literature, art, and music. Beyond that, Workman, who was fluent in French and German, believed settling abroad would allow her room to shape a new identity and afford her more independence to live her life as she saw fit, rather than under what she thought would be constant scrutiny back home in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Did you research any German sources for your book?

This was the first book I’ve written in a while where I didn’t use German language sources for research. I used French, Swedish and English.

How did her knowledge of German and French spread her reputation as an adventurer?

Her language skills helped her gain access to some of the most prestigious geographical and explorer societies, such as the Royal Geographic Society of London, whose past members included Charles Darwin, Richard Francis Burton, and David Livingstone. Workman addressed audiences throughout France, including Lyon and as previously mentioned she spoke at the Sorbonne. Her fluency allowed her to be interviewed by the local press as well.

What difficulties did Fanny Workman encounter in her adventures?

There were so many! When she cycled there were the punctured tires, sometimes as many as three in one day. In the Himalayas there was the weather, burning sun to subzero temperatures, the constant threat of injury and death, and the need to have to bring every single item with them. One has to do that now of course, but in her day there was no lightweight, weather resistant gear or dehydrated food.

And then there was the sexism. On the mountain there were recalcitrant guides who did not like working for a female leader, there were customs officers and boat captains who thought exploring was the domain of men. Off the mountain there were professional societies who didn’t believe women should be given the same due as men.

Did Fanny Workman ever become a victim of a crime?

On two separate occassions, while cycling through Algeria, robbers ambushed Workman and her husband. But she kept a pistol in a pocket sewn on the inside of her skirt and so when the men tried to rob and beat the couple she brandished the pistol and the men retreated.

What role did she play in women’s liberation?

When the Royal Geographic Society hesitated at the idea of her addressing its members because she was a woman she was not deterred. She took it as a challenge and became the second woman to address the Royal Geographic Society of London. When guides and porters on the mountain balked at her leadership she ignored the sexism and turned her attention to the tasks at hand, proving them wrong.

Workman held that women should live a life that was right for them not the life society deemed correct. While for Workman that meant marriage, motherhood and pursuing her passion, which she turned into her career, she understood other women might feel differently. Workman’s achievements are undoubtedly impressive, yet, I think the real message underpinning her story is how she navigated and bucked tradition, living a life with purpose and determination.

A very interesting story – thank you! However, it seems clear that her husband – who is not even dignified with a name here – must have done a great deal to support and enable her. Why not acknowledge that?

He did, but he was also comfortable with taking the backseat to her accomplishments. I can’t help but wonder if there is a double standard here. If I were to write about a man and his accomplishments, I can’t help but wonder whether I would get comments that I should have mentioned his wife. Let Fanny Workman’s accomplishments stand alone. Thanks for commenting, though!

Unfortunately, i am fairly convinced she was plain evil. There’s an article about wet nurses on JSTOR that describes a letter from her , complaining about her “ugly” nurse that she fired after the nurses baby died.

That sounds awful. I didn’t know that, and thanks for commenting. That rounds out the picture of Fanny Workman.