Eighty-six years ago, in August 1932, a highly unusual crime put the felony murder rule, an old law in Mississippi case law, to the test. That night, Emily Burns accepted an invitation to take a walk with one of her boarders. The 37-year-old widow rented out rooms in her home to other members of the black community in Natchez, Mississippi. What she didn’t know was that her boarder, who went by the nickname “Pink,” had made plans to burglarize a home that night.

An unplanned murder

Pink led Emily through the woods and bayous to a dilapidated house known as “Goat Castle,” where he met his two white accomplices. When Emily overheard them talking and realized their plans, she wanted to leave, but Pink threatened to kill her if she did. They snuck over to the house of a neighboring white woman and Pink motioned to Emily she should keep a lookout.

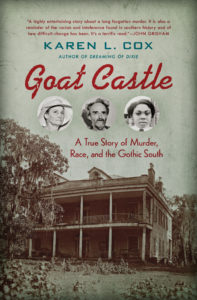

While Emily Burns waited outside, Pink and his white companions did the unthinkable: they murdered the occupant of the house. Pink made her hold the lantern while he and his accomplices carried out the body and deposited it 100 yards behind the house. Then they went home. That was the extent of Emily’s involvement. The law’s out-of-proportion reaction to Emily Burns is the subject of a recently published book, Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South by history professor Karen L. Cox. She joins us for an interview below.

A case that made national headlines

The investigation into the murder of 68 year-old Jennie Merrill of Natchez, Mississippi, made national headlines. That she was born into the southern planter aristocracy and her father was once U.S. Ambassador to Belgium were enough to garner attention. Yet the story that emerged focused on those charged—her eccentric neighbors, Dick Dana, 61, and Octavia Dockery, 68, also born into elite southern families except that by 1932, they lived in squalor in a crumbling down antebellum mansion with all variety of animals, including goats. Their home was nicknamed “Goat Castle” and the pair became known as the “Wild Man” and the “Goat Woman.” Journalists compared their story to those of Edgar Allan Poe and William Faulkner—a southern gothic narrative come to life. And despite the collection of their fingerprints from inside Merrill’s home, the case never went to trial. Instead, as was typical of the Jim Crow era, the black community was targeted. In the end, the only person to be punished was an innocent African American woman named Emily Burns. She was convicted as an accessory to murder and sentenced to life in prison in the state penitentiary—Parchman—while Dana and Dockery profited from their notoriety. Burns’ sentence was eventually suspended in 1940, and she returned to Natchez. Previous accounts of the case are terribly brief, and focus exclusively on the white principals. This book offers the first extensively researched account of this Depression-era crime, including the national media coverage, while also recovering the story of racial injustice.

The felony murder rule

The legal doctrine that allowed Mississippi to convict Emily Burns of murder is the common-law felony murder rule. It holds a person responsible for murder if someone dies during the commission of a felony, even if that death wasn’t planned.

Felony murder definition: The unlawful killing of another human being while engaged in the commission of or attempted commission of one of several felonies specified according to the laws of a particular jurisdiction. At common law, the “felony murder crimes” are burglary, arson, rape, robbery, and kidnapping.

The rule itself genders controversy. Not every U.S. state follows it. England, Wales, Ireland, and Northern Ireland have abolished it.

What makes the Goat Castle case different is the unbalanced punishment: Emily Burns took the legal blame for the murder while the white accomplices who were in the house when Jennie Merrill was murder got off scot-free. This gritty story is about what happens when the cogs in the wheels of justice run in the wrong direction.

Welcome Karen L. Cox! Dr. Cox is a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Interview with Professor Karen L. Cox

AMA: What role did Emily Burns play in the murder?

KLC: Emily was caught in a terrible situation. She accompanied the actual trigger man–George Pearls a.k.a. Pinkney Williams–on a walk the evening of the murder. Once he informed her of his plan to rob Jennie Merrill she tried to go home, but he threatened to kill her. So her role in the robbery was to stand watch outside of Merrill’s home. There she heard scuffling and shots–including those that killed Merrill. Later, she allegedly carried a lamp that lit the path for Williams to dispose of the body.

Did she ever enter Jennie Merrill’s house?

I don’t believe she ever entered the house. Her fingerprints were not found inside of the house. I feel certain if they had been found, that evidence would have been used at her trial.

Do you think justice was served in this case? Why or why not?

No, absolutely not. Emily Burns was the only one charged and convicted as an accessory to murder with very little evidence. Jennie Merrill’s neighbors, on the other hand, got off scot-free and their fingerprints were found inside of Merrill’s home. The fact that the fingerprint evidence was never discussed in court indicates that the DA did not want to try two white people; rather, he sought justice through the conviction of a “negro.”

Why do you think this story attracted national attention?

During the Depression, true crime sold newspapers and magazines and served as a cheap form of entertainment for Americans during desperate economic times. Such stories frequently involved the demise of prominent individuals and were fixated on the salacious details of family dysfunction. The murder of Jennie Merrill in Natchez, Mississippi, had all of this and then some. She was referred to as an “aristocratic recluse” and the way her neighbors lived led journalists to compare what was happening in Natchez as something that could have come from the pen of William Faulkner or Edgar Allen Poe—except it was all true. Thus, Natchez provided readers with two distinctive, and yet popular narratives, of Old South grandeur as well as southern gothic.

People have noticed similarities between Goat Castle and the more famous Grey Gardens. How do the two compare?

Analogies have been made between Goat Castle and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and the film Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte, too, but perhaps the best comparison is with Grey Gardens. Like Grey Gardens, Goat Castle is the name of a house and specifically a fine house that, by the time the public learned about it, was in shocking condition. Both homes had fallen into wrack and ruin, both were filthy and full of garbage and debris, and two people who were clearly not in their right mind occupied both houses. There is also the similarity that despite the years and the location that separate these two estates, Goat Castle, like Grey Gardens, is a story of the social and economic downfall of elites—in this case, people descended from the planter class of the Old South.

Given that you’re a white woman writing about a black woman, you needed access to Emily Burns’s community. How did you gain their trust to get them to open up to you and thus do Emily’s story justice?

This is an important question, especially given the racial history of Natchez and Mississippi more broadly. As a white woman telling a black woman’s story, it was important to get the perspective of the black community and I could best do that by talking with people in person, in places where they felt most comfortable, and demonstrating my appreciation for the gift of the information they shared with thank you notes, phone calls, etc. Because the church is such an important institution in the black community, I also attended services at Emily’s home church in Natchez and spoke directly to the congregation about my efforts to bring justice to her story, promising to return and share the book with them when it is published—a promise I intend to keep.

Goat Castle can be characterized as both Southern history and true crime. How did your training as a historian inform your work as a writer of true crime? Did you have to adapt your writing style in any way?

I’ve long been fascinated by local stories, and so my training as a historian helped here because it meant digging into local records for even the tiniest bit of information that I could then piece together to understand more about the individuals involved. Census records, city directories, witness dockets, case files, maps, and the landscape itself all provide information. In fact, I think of a book, and particularly this story, as a puzzle. Once all of the pieces are put into place, an image emerges or, in this case, the story emerged. I absolutely adapted my writing style. While my training would suggest I should write a scholarly work, this simply would have ruined the story I was trying to tell. So, while I did the primary and secondary research one would expect a historian to do, I wrote a narrative with a more general audience in mind. A true crime story about a place named “Goat Castle” required this approach.

Thank you, Karen L. Cox!

What do you think of the felony murder rule? Was it justly applied in this case? Should it be abolished?

PUBLISHING DETAILS

ISBN 978-1-4696-3503-3 $26.00 cloth

240 pp., 24 halftones, notes, bibl., index

Publication date: October 9, 2017

For more information: http://uncpress.unc.edu/books/13265.html

Portions of this blog post were borrowed from “A conversation with Karen L. Cox, author of Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South” (University of North Carolina Press, Fall 2017). The text of this interview is available at https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B_J0IYnVH90QSHRnemxLUFEwS3c.

A brief youtube film about this case, posted the Natchez National Historical Park, shows pictures of many of the participants and places.