Manifest Destiny

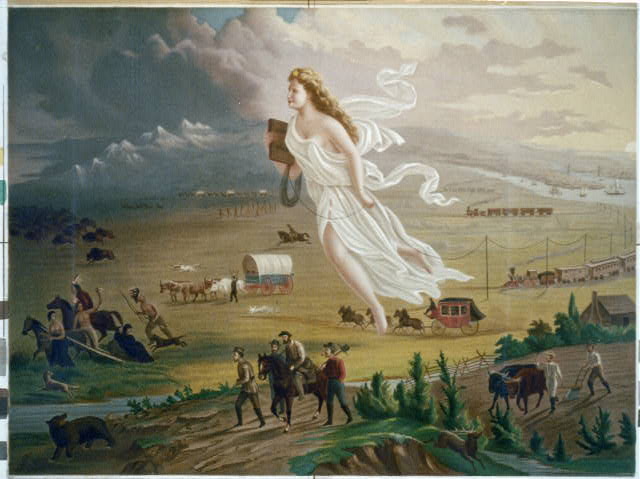

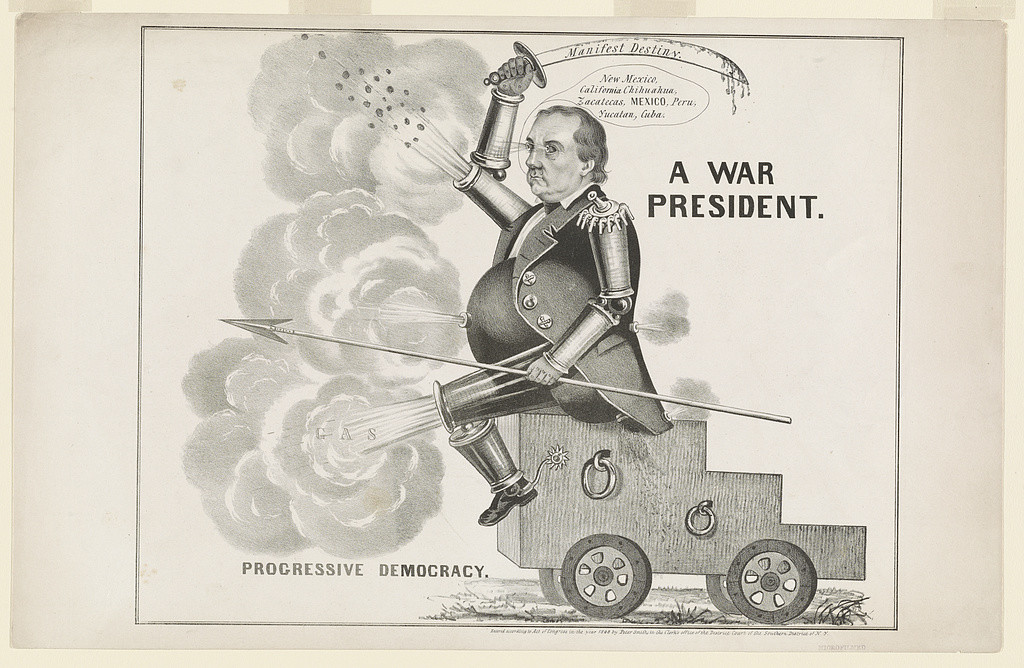

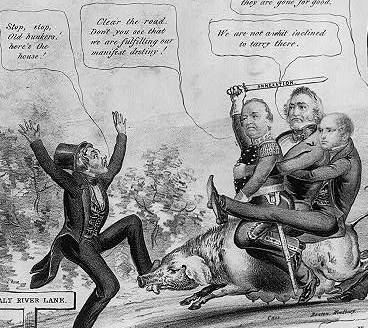

It’s impossible to read a history book covering the two decades preceding the Civil War without encountering this phrase. And for good reason: Manifest Destiny shaped American politics in the 1840s and propelled the United States into the Mexican-American War, the results of which led to the Civil War.

Manifest Destiny is the belief that the United States had a divine mandate to occupy the continent from coast to coast. But who coined the term? That’s the subject of an academic debate.

In 1927, a historian names Julias Pratt decided to track that question down. He traced the first use of the phrase back to an article in the August 1845 issue of the Democratic Review. The piece, called Annexation, discussed the annexation of Texas and maintained that England and France were The United States’ true enemies, “thwarting our policy and hampering our power, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence….” Because the article was unsigned, Pratt assumed John L. O’Sullivan, the editor, had written it.

Who was John L. O’Sullivan?

O’Sullivan (1813-1895) was a lawyer and political journalist who founded the Democratic Review. As editor, he published political essays by prominent authors. O’Sullivan was at the peak of his career when the article containing “manifest destiny” appeared. One month later, he hired editors to take over his position while he travelled to Europe. He returned in late December, and a month later, in January 1846, the paper’s investors fired him.

Later in 1846, O’Sullivan moved to Cuba, from where he agitated for Cuban independence. That landed him in front of an American jury on charges of violation of the Neutrality Act, but the jury couldn’t reach a unanimous decision. President Pierce later appointed John L. O’Sullivan as a diplomat to Portugal. Thereafter he had trouble finding a job. He died in poverty in New York from a bout of influenza.

Another Theory

In 1999, Linda S. Hudson advanced a new theory in her Ph.D. dissertation: It wasn’t John L. O’Sullivan who coined the term “Manifest Destiny,” but a female journalist, Jane McManus Storms. Hudson conducted a computer-assisted textual analysis of material known to have been written by O’Sullivan and Storms and compared them to the anonymous Annexation article in which the term “manifest destiny” first appeared.

The results were statistically significant. O’Sullivan’s writing had a 41.5% similarity to Annexation, whereas Storm’s 79.6%. Women writers of the era typically published anonymously. That’s why the article was unsigned, explains Hudson. Hudson also points out Storm’s intense interest in the Texas question – she had lived in Texas and purchased land there. O’Sullivan, on the other hand, was preparing to chase the woman he eventually married to Europe, and in August 1845, his mind probably wasn’t on politics, but on love.

Hudson went on to become a professor of history and published a biography of Storms called Mistress of Manifest Destiny. Her conclusions have found some acceptance. The recently published Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War also credits Jane McManus Storms with coining the phrase “manifest destiny.”

But acceptance is not universal. Robert D. Sampson, a John L. O’Sullivan biographer, points to the pitfalls in computer-aided textual analysis and questions whether a program designed to analyze late 20th century texts can validly be used to assess mid-19th century texts, especially since rules of grammar hadn’t then been formally established. Most importantly, Sampson contends Hudson used a text as a basis for O’Sullivan’s writing that his mother had written.

Sampson’s concerns are valid. They are signposts for further research on the question of authorship. At the very least, the academic debate introduces us to a little-known American journalist whose life was so adventurous, it’s interesting to read about her whether she wrote Annexation or not.

Jane McManus Storms

Jane McManus Storms (1807-1878) was an editor and journalist who publised 100 columns in various American papers, along with 20 journal articles and book reviews, and 15 books. She usually published anonymously or under the name “Montgomery.”

But her life gets really interesting in the Mexican-American War. Think Bond.

Jane Bond.

Storms’s knowledge of Spanish and Latin America convinced President Polk to send her along with a New York editor and a Catholic bishop to Mexico City in January 1847 on a secret mission to negotiate a peace treaty. They entered Mexico from Cuba to arouse less suspicion. From Veracruz they traveled to the capital, only to find it on the cusp of civil war. During this period, Storms wrote reports for the editor’s newspaper in New York. She was the only American war correspondent working from behind the Mexican lines.

When fighting broke out in Mexico City, the secret agents fled. Jane McManus Storms left before the men did, taking a hazardous 200-mile trip to Veracruz, where General Winfield Scott of had started a siege. Storms met with Scott, advised him of the political turmoil in the capital, and suggested a route the U.S. Army could take there. Scott ended up following her route in his conquest of Mexico City.

Storms later married and lived in both Texas and the Dominican Republic. Her death was spectacular as her life. She drowned when the steamer she was taking to San Domingo sunk in a storm. Two sailors who survived later spoke of Storms facing her death with resignation.

There are no known images of Jane McManus Storms. Someone with the same last name has her husband (Cazneau), however, had posted an image on the Find a Grave Site. Storms was known to have a dark complexion and violet eyes.

What do you think of the two theories about who coined “manifest destiny?”

Literature on point:

Linda S. Hudson, “Jane McManus Storm Cazneau (1807-1878): A Biography,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Univ. of North Texas, 1999

The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2013)

Tom Reilly, War with Mexico! America’s Reporters Cover the Battlefront (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010)

Robert D. Sampson, John O’Sullivan and His Times (Kent: Kent State Univ. Press, 2003)

What a fascinating story. And Ms. Storms could easily be the heroine of a series of adventure novels. She sounds like a splendid woman.

I agree! She led such a fascinating life, and it was even more amazing that a woman could have played those roles in the 19th century.

How many things unknown women probably could be credited with. Thanks for sharing this!

I suspect there’s a lot, Linda. In the past, men sometimes took credit for women’s accomplishments, even with the women’s permission, because then the idea had a better chance at recognition. Thanks for commenting, Linda!

Thanks for this, Ann Marie. I wallow in 19th century history myself and have never heard about Storms. I appreciate the education.

Thanks, Keith! I appreciated learning about Storms myself. In this post, I could only skim the surface of her life.

I love the way you track this down, Ann Marie. I’d rather not attach this idea to a woman who sounds admirable and brave. Manifest Destiny. Such beautiful words. Such a lousy idea, no matter who came up with it. The United States still suffers from thinking we know it all, God is on our side, and we must lead the way. What a mess we make.

No matter who coined the phrase, Elaine, I doubt the person had any idea of the historical consequences of the idea and the words. But change history they did. Thanks for commenting, Elaine.