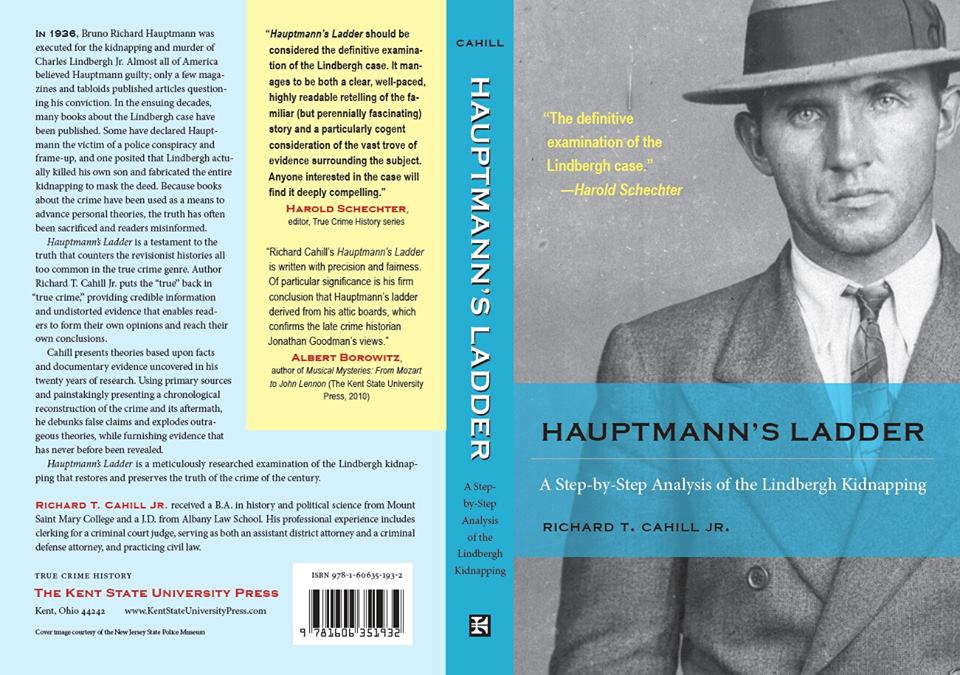

Real quick now – which saint killed the dragon? What’s the first name that comes to your mind?

St. George. Is that what you thought?

It’s what I thought, too. St. Mark’s Square in Venice sports two monolithic columns with figures on top. One is a winged lion and the other a man killing a dragon. St. George, I assumed, when my husband and I visited the square. I mentioned it to our gondolier.

“No! Not St. George!” he said. “It’s San Marco. San Marco is Venice’s patron saint.”

“St. Mark also killed a dragon?” I asked.

He shrugged his shoulders. “I dunno. But it is Marco. Not George.”

St. Mark, the winged lion of Venice

His answer made sense. Venetian merchants, according to legend, stole the relics of St. Mark the Evangelist from a church in Alexandria in 828. They brought the bones back to Venice. (Some scholars claim the merchants made a major blooper and actually made off with the skeleton of Alexander the Great!) St. Mark’s relics now reside in Venice’s Basilica di San Marco. The winged lion is a symbol for St. Mark, so that explains the figure on the other column.

But my quick perusal of St. Mark’s history revealed nothing about dragon mythology.

St. Theodore of Amasea and the dragon

Are gondoliers really infallible when it comes to Venice’s history? Maybe not.

You can imagine my surprise when I checked our guide book back at the hotel. It said the dragon slayer at St. Mark’s Square was St. Theodore. I’d never heard of the fellow, but the author said Theodore, a simple Greek soldier and minor saint, was Venice’s patron before Mark’s relics made the trans-Mediterranean trip to the floating city. St. Theodore enjoyed more popularity in the Eastern Orthodox Church. But in the west, he was too minor a martyr for Venice. The Venetians felt compelled to search for another patron in 828. They wanted someone who could offer more protection.

The Eastern Orthodox Church holds the clue to the dragon. Theodore’s iconography often shows him spearing the vile serpent. And sometimes Theodore’s even depicted accompanying St. George.

So that’s where the dragon comes in. The two columns, with the dragon slayer and winged lion, represent the floating city’s two patron saints. That makes sense, right?

Mark Twain in Venice

Enter Mark Twain. He visited Venice in 1878 and came up with a more charming explanation for the winged lion of Venice than any historian ever did. It came to him while he was viewing Tintoretto’s painting Paradise in the in the Doge’s palace. It offers a view of heaven.

There are fifteen or twenty figures scattered here and there, with books, but they cannot keep their attention on their reading – they offer the books to others, but no one wishes to read, now. The Lion of St. Mark is there with his book; St. Mark is there with his pen uplifted; he and the Lion are looking each other earnestly in the face, disputing about the way to spell a word – the Lion looks up in wrapt [sic] admiration while St. Mark spells. This is wonderfully interpreted by the artist. It is the master-stroke of this incomparable painting.

Lions, in the form of statutes, paintings, and even the city flag, are everywhere in Venice. They’re often depicted holding a book. If Mark Twain is right, that book isn’t a Bible. The winged lion of Venice is holding a dictionary and trying to help us with our spelling. And that gave me a whole new way of interpreting Venice’s artwork.

Here the lion is poised on the bow of the royal barge in Venice’s naval museum, announcing to the world that the royalty, of all people, knew how to spell.

You can see by his expression in this picture how disgusted the winged lion of Venice is with the chap to the left. He must be a really bad speller.

In St. Mark’s Square, the lion also appears to have given up on St. Theodore. He’s facing in the other direction, looking out on the tourists, hoping to find a writer among them. And if he does, he whispers down letters to them; he breathes long-sought words across the expanse of the piazza.

I like that lion. And thanks to winged lion of Venice, I’ll never see my dictionary the same way again. From now on it will have soft, golden fur and outspread wings, ready to take my writing to greater heights. And should I ever misspell a word, I expect it to roar and bite me in the buttocks.

As it well should.

Did you notice Twain’s spelling error? Do you think he did it on purpose? Is this another example of Twain’s sly sense of humor?

Literature on point

Jenny John, Venedig (Munich: Gräfe und Unzer, 1997).

Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad (public domain).

Your article link was posted in our Google+ writers group. Very interesting and entertaining. LOVED it. I will never look at lions the same again either. Thanks for a happy smile this morning.

Thanks, Tam! Twain’s comments about the lion were so charming they changed the way I looked at the Venetian art!

This was a wonderful post! I’ll have to hope he whispers to me next time I’m in Venice 🙂

I’m sure he will, Icy! He helped give me the idea for this post, so I’m very grateful to him.

I couldn’t resist Mark Twain and St. Mark and St. George. Was it a spelling error with a particular message? I lived in Mexico, MO when I was a child and each year my school took students for a field trip to Mark Twain Caves in Hannibal, MO. Now I live 20 miles from Elmira, NY where Samuel Clemens had a summer home and where he’s buried. I always loved his sense of humor.

I was in Venice. I didn’t see most of those winged lions. Twain would, and you would. Thanks for sharing the secrets.

You’re lucky, Elaine, to have had such a physical connection to the localities in Mark Twain’s life. A wonderful author like Twain is always worth a re-read; each time I see something new (like his spelling error in the middle of his discussion about spelling). Was that a conscious error meant to convey a particular message? Hmmmm. Good question. Twain might have used a word play with “rapt” and “wrapped,” and might “wrapped” (the old spelling was “wrapt”) have a hidden meaning in context? I’ll have to think about it.

Look for the lions the next time you’re in Venice. If you don’t find them, they’ll find you and offer you some writing tips. Thanks for commenting!

Wonderful post – made me smile and consider whether to bring out my big stuffed lion from retirement 🙂

Definitely do, Anna! I’m sure your big stuffed lion would have some interesting things to whisper to you. Thanks for commenting!

A spelling lion? Well I never! I laughed so hard at this that I nearly choked on my water. I had always assumed that the lion was a symbol of naval power but this is a much better interpretation. Although now, I’m suddenly scared to spell a word wrong ever again

Thanks so much for your comment, Srini. It made my day today.

[…] Also called Piazza San Marco, it is Venice’s main public square, basically the social heart of the city. There are a bunch of famous landmarks here, like the Clock Tower, St. Mark’s Basilica, Doges’ Palace, and the Winged Lion of Venice. […]

Venice, without a doubt, is worth a visit.