Technically, it wasn’t a crime.

The Philadelphia shopkeeper was just looking for a way to make money, and as long as the United States hadn’t recognized the Confederate States of America, he could legally produce them. And they may have had done more damage to the Confederacy than Yankee bullets.

Counterfeit Confederate Currency as Souvenirs

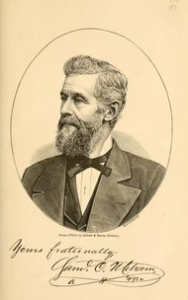

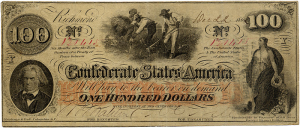

Sam Upham originally sold his replicas of Confederate bills as curios, “mementos of the Rebellion.” He stamped the bottom edge of each bill with a notice: “Fac-simile Confederate Note – Sold Wholesale and Retail by S.C. Upham, 403 Chestnut St. Philadelphia.”

Fake $5 notes, black-and-red handiworks depicting five goddesses, Agriculture, Commerce, Industry, Justice, and Liberty, went for a penny apiece. They sold like “hotcakes.” Upham then upgraded to $10 bills, selling a pack of 100 for $2 and advertising them in the newspapers.

That’s when dishonest cotton smugglers took notice. They snapped up Upham’s bogus scrip in bulk, trimmed off his disclaimer at the bottom, and passed them off as real Greybacks in the South, where they purchased cotton with Upham’s kickoffs and smuggled it back through the battle lines to sell in the North. As Upham started making money, he started printing higher denominations, and even more counterfeit Confederate currency floated south.

Federal agents heard rumors about Upham’s counterfeiting business and paid him a visit. But as far as they were concerned, he wasn’t doing anything illegal as long as he wasn’t forging Greenbacks.

Counterfeit Confederate Currency and Inflation

As the war continued, inflation devoured the value of the Confederate banknotes. At one point, each Greenback was worth 1,200 Greybacks. Upham claimed his knockoffs waged a fiscal war with the Confederacy and did more to help win the war than bullets ever did. Confederate Senator Henry Foote agreed, in part. He told the rebel Congress that Upham did more damage to the Confederacy than General McClellan ever did. Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, Christopher Memminger, took note of Upham’s scheme and suspected an organized Yankee scheme behind it.

A modern economic analysis corroborates some of Upham’s boasts. Upham printed about 15 million forged banknotes, amounting to 1-2.5% of the Confederate money supply. “The … evidence indicates that Upham’s counterfeiting business had a significant impact on the Confederate price level,” writes economist Marc. D. Weidenmier. “Counterfeiting fueled the Confederate inflation via a large increase in the money stock….”

Upham wasn’t the only counterfeiter in the war. Winthrop Hilton also produced bogus Confederate scrip in New York, but his scheme backfired. Federal agents thought he was producing the real thing and jailed him for printing authentic Confederate bills north of the border. They thought he was cooperating with the Rebels. Entrepreneurs in Havana, Cuba, printed phony Confederate bills and smuggled them into Florida.

Did the Rebels Strike Back?

If the Rebels were aware of Yankee counterfeiting schemes, did they ever try to strike back by counterfeiting Greenbacks? I haven’t seen this question discussed anywhere. It’s possible that Greenbacks were simply harder to replicate. The Confederacy used lithographic printing, whereas the United States employed high quality engravers. The former process is cheaper, but easier to fake. Lithographic technology might have become one of the swords on which the Confederate currency fell.

Using bogus money as paper bullets was nothing new. Britain tried to undermine the American economy during the Revolutionary War by mass-producing counterfeits. In New York Tory newspapers, it advertised “any Number of counterfeit Congress-Notes, for the Price of the Paper per Ream.” During WWII, Nazis put prisoners to work creating counterfeit Allied money. They hoped to weaken the enemy economy.

When you sweep all the price charts and currency rates aside, one thing remains as clear as cannon fire on a windless night: Battlefields were not the only arena on which the Civil War was fought. Ordinary people made a difference.

Can you think of other ways people fight wars off the battlefield?

Literature on point:

Tobin T. Buhk, True Crime in the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books 2012).

Jack Lynch, The Golden Age of Counterfeiting, Colonial Williamsburg Journal (Summer 2007) (quote about British counterfeits)

Marc D. Weidenmier, Bogus Money Matters: Sam Upham and his Confederate Counterfeiting Business, Business and Economic History 28(2):313-324 1999 (quote pp. 320, 321).

I wonder what’s worth more today – the legit or counterfeit bills?

Whichever one is more rare?

Upham’s counterfeits are worth more today. I guess he got the last laugh.

Fascinating article. I had to dig out some old bills from the Civil War era. I have confederate bills but how can I tell what’s counterfeit and what’s not?

Fascinating that you have some old Confederate bills, Jill! I can’t tell the difference, so if you want to know if you have real or counterfeit bills, I’d get a professional appraisal. But either way, the bills are worth something.

The best way to tell if Counterfeit is by using Rapheal Thian’s book, Register of Confederate Debt. He was tasked with finding out just how much Confederate notes were printed. It took him thirty years to publish.It has all the signers both for Register and Treasurer for specific Notes via serial numbers and letters.Another good reference is George Tremmels book

Thanks for that tip!