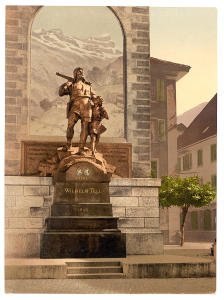

No other arrow in history has set so many quills into motion as William Tell’s apple shot. Tell’s composure and courage have thrilled composers and poets alike. Rossini’s overture and Schiller’s dramatization are only two expressions of admiration. The Tell legend may well be the most famous crime story ever told.

But the apple shot was just the first arrow. Tell’s next arrow found a different mark. It flew into the law library, disappearing into a gap between the paragraphs delineating murder and justifiable homicide. Seven hundred years after Tell released that arrow, scholars are still debating whether Tell’s shooting Albrecht Gessler was murder or not.

Let’s recap the story. Austria sought to dominate Switzerland in the 14th century and set up Albrecht Gessler as the Austrian magistrate of the Swiss city Altdorf. Gessler erected his hat on a pole on the town square and demanded that the townsfolk venerate him by bowing to his hat. William Tell, a resident of a neighboring Swiss town, visited Altdorf in 1307 with his son and refused to take the bow. Gessler arrested him. Because Tell had a reputation as an expert shot with his crossbow, Gessler decided the appropriate punishment would be to have Tell prove his prowess by shooting an apple from his son’s head. He forced Tell in the only manner anyone could ever compell a parent to fire a weapon in his child’s direction: by threatening to kill both if Tell didn’t comply.

William Tell slipped two arrows out of his quiver, and with the first, shot the apple. But Gessler wanted to know why Tell needed a second arrow. “I would have used it to shoot you,” said Tell, “had the first arrow struck my son.” Angered, Gessler had Tell bound and carried to a ship to transport him over Lake Lucerne to a dungeon in Gessler’s castle.

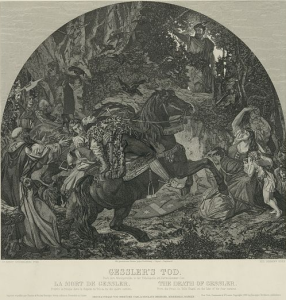

A raging storm made steering the boat nearly impossible, so the crew unbound Tell to have him help. As the ship passed near the shore, Tell took the opportunity to leap overboard and escape. He then ran to Gessler’s castle and ambushed him in the woods on his way home. Gessler was killed with William Tell’s second arrow. That action sparked a rebellion that led to the birth of the Swiss nation.

Some scholars defend Tell, relying on the ancient Germanic rights of Notwehr and Selbsthilfe (self-defense and self-help), rooted in Roman law. But as with modern law, these rights permit self-defense only as long as the threat persists. But William Tell, lurking in the woods to ambush Gessler, could not claim he was still under direct threat.

Others defend Tell with the German Widerstandsrecht, or right to resist an oppressive government. This right, however, is murky. It is perspective, or the outcome of a war, that separates the hero from the villain. No doubt Austria would have considered Tell a traitor had it conquered Switzerland. Nothing illustrates this point as well as John Wilkes Booth’s diary. America’s greatest villain devulged that William Tell was one of his role models for the Lincoln assassination. Booth thought he was relying on the same right. But can we exonerate Tell based on the right to resist and still condemn Booth?

A modern defense of Tell might center on temporary insanity. Can anyone expect a father who has been forced to shoot an apple from his son’s head, and watch his own child’s emotional turmoil, to function normally in the hours and days following? A lawyer could underpin this argument by painting Gessler’s apple shot coercion as a war crime.

Finally, some critics insist that Tell’s act was pure revenge — an act of premeditated murder. The irony of the Tell story, they say, is that it suceeds in getting the reader to rejoice over Gessler’s death. It makes us feel good about a murder.

What do you think? If you were on a jury and this case came before you, how would you vote? Murder or justifiable homicide?

Literature on point:

Gail K. Hart, Murderous Fathers: Wilhelm Tell and the Decriminalization of Murder; in: Gail K. Hart, Friedrich Schiller: Crime, Aesthetics, and the Poetics of Punishment (Newark: University of Delaware Press 2005)

Hans-Jörg Knoblauch, Wilhelm Tell; in: ‘Schiller Handbuch, Helmut Koopmann, ed. (Stuttgart: Alread Kröner Verlag 1998)

Text (c) 2014 Ann Marie Ackermann

I had to google William Tell to check if he was Swiss and not a foreigner passing through. I’m not too familiar with the history of this area. If Austria invaded Switzerland and this was “war” and Gessler was an oppressive invader then killing him was A-OK. Case dismissed.

But I can write up about 10 other ways of looking at it too.

You’re right, Brian. I was just thinking — right before I read your post, that one could categorize Tell’s second arrow as the first shot in the Swiss war for independence. But of course, the line separating war heroes from terrorists is a thin one, dependent on the outcome of the war. That’s what makes it murky — it’s not a measuring stick you can use to evaluate the act at the time it’s committed. But history has most certainly deemed Tell a national hero.

I’ve edited the post to clarify that Tell was Swiss. Thanks for pointing that out.

I remembered only a little of the William Tell story, so thank you for the recap. Ann Marie, your writing style and the photos make this story sing.

They would not allow me to sit on the jury because I’d say I don’t condone violence coming from anyone or either side in a war. An idealist can hold this simple position when no one shoots bullets at her home or arrows at her children.

Thanks so much for the compliment, Elaine. I enjoy writing these blogs.

Today we would call Gessler’s treatment of Tell a war crime. I don’t condone violence either, but I can understand how the stress of being forced to shoot arrows at my child might make me act differently. One of Friedrich Schiller’s hallmarks as an author was to select “crime” cases in which the reader’s sympathy for the offender is so strong the reader wants to exonerate him or her. William Tell and Joan of Arc are two examples of Schiller’s “true crime” characters. A lesser known one is “The Criminal Motivated by Lost Honor.”

I get it. Seems there may be many such crimes where I empathize with the offender–such as giving a dying & suffering person a little morphine boost to help them get to the other side. Some call it murder. Others call it mercy. I’ll look at “Lost Honor.” And, yes, Joan of Arc. How can we not love her?

That’s precisely why Schiller stood out from other authors, who focused on sensationalism (not unlike modern true crime authors). And it’s also why the world still reads Schiller today and all those sensationalist stories of the 18th century have been forgotten.

As soon as my kid is safe Gessler is a dead man, threaten my kids and not an idol threat. Dead man walking

And I think most people would feel the same way, Big b!

All the heroes of the American revolution would have been hanged as traitors and murderers had they been caught. That was also the date of John Brown after his failed raid on Harper’s Ferry just before the Civil War.

Yes, exactly! Or think of the man who fired the first shot in the Civil War (I forget his name). I consider Tell’s actions an act of war, and usually you don’t go back and prosecute people for murder after a war. The Nuremberg Trials are a rare exception, but that involved other issues. Thanks for commenting, Ed.

I learn from every story that you write, thank you so much! I didn’t know the story of William Tell other than the very basic fact that he had to shoot the apple off of his son’s head. I know that in modern times you have to be in immediate danger or your family is in immediate fear of their lives, but it seems like justifiable murder to me. I wonder if he had done the same to others, plus Gessler was also a cruel man for wanting to imprison William Tell probably for the rest of his life even though he had a son. Thanks for also bringing it up that it might be seen as fighting against an oppressive government. Gessler was definitely oppressive. Very interesting story, thank you.

I find this history fascinating too, Susan! Any parent must have realized the extreme anguish Tell suffered. Even if it may have not counted as self defense, that anguish would have continued and could have contributed to a temporary insanity defense today. But more likely, Tell’s actions would have been considered an act of war — the opening shot in the Swiss movement for independence. And usually you don’t go back and prosecute people in a war for murder. Someone has to fire the first shot….

Justifiable homicide, at most… and I would say, EXTREMELY justifiable homicide! To compel a parent to set the life of his child at risk – and at his own hand – is an egregiously vile act, and I am old-fashioned enough to invoke honour as much or more than “temporary insanity.” It’s not like Tell could have taken Gessler to court to get satisfaction!

And, yes, definitely the first shot in a war. The comparison with Booth is an interesting one! You ask, “can we exonerate Tell base on the right to resist and still condemn Booth?” I am inclined to say “no, and therefore we should not condemn Booth, either!” But as you say, the victor writes the history, and makes the rules…

One important difference, of course, is that Tell’s shot started the war; Booth’s came at a time when the war was already lost. Had the latter done his deed in, say, late 1861 or early 1862, perhaps things might have turned out rather differently. Who can say?

Thanks for commenting, Tom. Your point about Booth is interesting. Yes, the circumstances were different.

It’s utterly absurd to compare Tell with Booth. One stood up to tyranny, the other stood FOR tyranny.

ROFL. ‘Debate’ only among smug self-important navel-gazing ‘scholars’. Of course it was justified rebellion.

If you view Tell’s arrow as the opening shot of the rebellion, you’re right on.

Coming late to this party, but, well… that seems trivial compared to the span since Herr Wilhelm Tell opposed the tyrant Gessler.

I find self in agreement with earlier commentor Mr. Kinory, that the dissection of fine distinctions in legalisms misses the point that Tyrants by their injury and breach of the rights of the population, have abandoned and demolished any legitimate claim to rule, and nor the protection of the Law.

Some may regard this view as an anachronistic modernism that should not be applied to the case of medieval Austrian domination of un-consolidated embryonic proto-Swiss society.

Poupon that, sez I. Tyrants is Tyrants in all epochs. In imposing his own vicious rule, Gessler lost the country for his Austrian masters. Maybe Gessler was no pirate of the seas, but he fulfilled the sense of “Hostis Humani Generis.”

In other words, all is fair in (love and) war. The tyrants incited a war, and then the law goes out the window. Which is what I tried to say above. Thanks for commenting.

I don’t buy the argument that the threat didn’t persist: it may not be a direct threat but any reasonable person would expect that Gessler would have had Tell killed if given the chance. And he certainly had the power. So, it’s a bit of a convoluted case of self defense but i do honestly believe that this was self defense.